Introduction to Buddhist Practice

Nirvana is the highest happiness…the Buddha, as quoted in The Dhammapada, verses 203 and 204.

If we complete this course, it will help us develop the Bodhi Mind – the aspiration to achieve enlightenment for the benefit of all sentient beings. If we have a desire to attain enlightenment for our personal benefit, we have a desire for something that is impossible because the belief that there is a self that is separate from all sentient beings is an impediment to enlightenment.

Paradoxically, Zen teaches that every sentient being is already enlightened. But our heart and mind are closed like a lotus in the dark. As the sun rises, the lotus opens, layer by layer until its center basks in the sunlight. Our enlightened self is like that – hidden under many layers of ignorance. We peel off those layers, like the layers of an onion, with daily practice.

Somehow the Eastern metaphor of a lotus opening layer by layer is a little more appealing than its Western counterpart of peeling off the layers of an onion. That is perhaps why the lotus is the symbol of Buddhism, and not the onion.

On a more mundane level, perhaps as our practice grows we’ll be able to remember past lives, walk on water (yes, that’s in the ancient Buddhist scriptures, too), and other amazing things.

But we don’t practice Zen to get something. We practice to cultivate wholesome states and to abandon unwholesome states.

The aim of all Buddhist practice is to cultivate wholesome states and to allow unwholesome states to wither away. Enlightenment is thus understood as wholesomeness, as distinguished from division and separation.

The self is a fragile bottle of water adrift in the ocean, a bottle that will disintegrate if it crashes onto a rocky shore. When the bottle disappears, the water in the bottle is inseparable and indistinguishable from the ocean; it has become whole and cannot be destroyed by a rocky shore or anything else.

Religions like the metaphor because according to religion it means that when a person surrenders his or her self to Christ, or God or a guru or whatever, that person becomes infinite and lives eternally. But Buddhism holds that even the ocean is finite and is always changing; nothing is eternal and unchanging. And nothing, no First Cause, no god, stands outside of that reality.

The Buddha was asked:

What makes you different from other people?

He replied:

I am awake.

The first step to “the highest happiness” is to develop happiness, of course.

Most people are surprised to learn that Buddhism is based on happiness. The people who announce that Buddhism is pessimistic don’t know squat about Buddhism. It’s the Christians who say that people have original sin and are corrupt and need to be saved from their inherent evil. Now that’s a religion based upon pessimism.

Buddhism takes the opposite viewpoint, i.e., that people are inherently pure, wholesome, and complete, just as they are. But we are asleep and don’t know it. That’s why the Buddha said he was different because he was awake.

Buddhism provides a specific technique for building the foundation of happiness upon which all of the rest of Buddhism is supported. An unhappy person has no hope of waking up.

We learn a happiness-building technique in step one of Beginning Zen. It’s called Present Moment Awareness.

If we skip Present Moment Awareness, we have no foundation to support the steps that result in awakening to “the highest happiness.”

The first step to happiness is to “put mindfulness in front of you” as taught by the Buddha in The Anapanasati Sutta. What that means has been explained by the Venerable Ajahn Brahm. He teaches that placing mindfulness up front is a two step practice; Present Moment Awareness is the first of those two steps.

[su_spacer size=”30″]

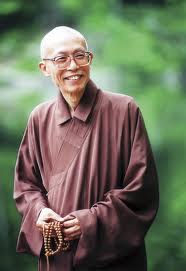

(now there’s a happy guy!)

Let’s get started! In less than an hour, we will know how to practice authentic Zen. We will be practicing mindfulness, which is the first factor of The Seven Factors Of Enlightenment. The other six factors are built on the foundation of mindfulness and can’t develop in its absence.

Mere suffering exists, no sufferer is found;

The deeds are, but no doer of the deeds is there;

Nirvana is, but not the person who enters it;

The path is, but no traveler thereon is seen.

[su_spacer size=”30″]

–chapter 16, section 90 of The Path of Purification

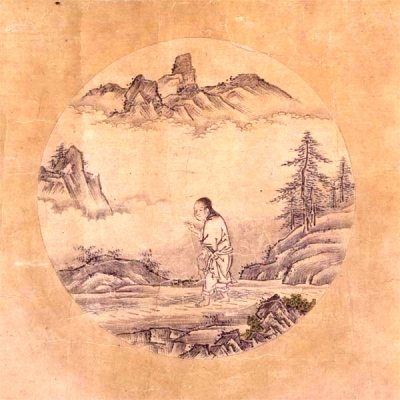

Step 1 – Seeking the Ox

The Tenth Dharma Realm

In the pasture of the world, I endlessly push aside the tall grasses in search of the Ox. Following unnamed rivers, lost upon the interpenetrating paths of distant mountains, my strength failing and my vitality exhausted, I cannot find the Ox. I only hear the locusts chirping through the forest at night.

Present Moment Awareness

Hearing Awareness hears the locusts chirping through the forest at night. The “I” has nothing to do with Hearing Awareness, and Hearing Awareness is not an entity or being.

We begin in the tenth dharma realm, the lowest of all realms. The central practice is counting exhalations in order to cultivate the happiness that is the antidote for the unhappiness that defines this bottom realm.

To seek the ox, we practice Present Moment Awareness as taught by Venerable Ajahn Brahm in Mindfulness, Bliss and Beyond.

Here are the preliminaries:

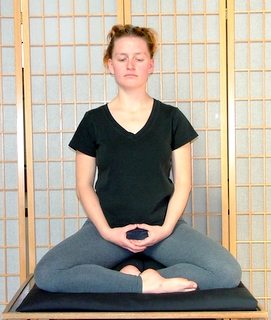

- We sit facing a wall, maintaining our eyes slightly open but not focused on anything, looking down with the eyes only so that the head is erect. This is the classic Zen meditation posture in a nutshell. Consult The Three Pillars of Zen for a more detailed description of postures.

- In keeping with both Zen and Theravada training, we try not to move during the sitting. When the body is moving, the mind is moving (an old saying).

- For beginners, we recommend the quarter lotus. We recommend the half lotus for intermediate practitioners and the full lotus for advanced practitioners.

- Most Zen teachers advise us to keep the eyes sightly open to ward off sleepiness. However, we don’t focus the eyesight on anything. If a hand were to be waved in front of our eyes, we would notice that. But we wouldn’t notice anything else.

- If we can remain alert and not sleepy with our eyes closed, it is OK to close the eyes.

As taught by the Venerable Ajahn Brahm, we begin Present Moment Awareness meditation by instructing our mind to:

- Forget the past;

- Drop thoughts of the future; and

- Experience only the present moment.

While seated on our meditation cushion, we can listen to birds chirping, street sounds, and so on, as long as we are only listening to the sounds of the present. We can enjoy the smell of incense as well.

Master Hakuin, over two thousand years after the lifetime of the Buddha, observed that modern (1700s) people did poorly when told to sit quietly in the present moment. So he developed a technique that involves counting the breaths and that’s a technique we can use to develop present moment awareness if the above instructions are too abstract.

So we come to our first merger of Theravada Buddhism and Zen Buddhism. We sit in present moment awareness as instructed by Venerable Ajahn Brahm of the Theravada tradition and then to deepen our present moment awareness we count our exhalations as taught by Zen Master Hakuin.

Counting our exhalations also prepares us for the Tranquil Wisdom meditation of Intermediate Zen, the meditation taught by the Buddha.

Master Hakuin’s meditation is a simplified version of what the Buddha actually taught but it’s effective. Many people have awoken to their inherent Buddha nature over the centuries by following Master Hakuin’s instructions. Its effectiveness and its power to awaken lie in its Zen simplicity.

We mentally count our exhalations from one to ten, and then we do it again. We don’t breathe out so that we can count an exhalation; we breathe naturally. If we are very calm and centered and hardly breathing at all, that’s fine. We just wait for the next exhalation and count it when it naturally appears.

If a breath is long, we mentally count it by extending whatever number it happens to be, such as threeeeeeee or fiiiiiive, and so on.

We don’t congratulate ourselves or celebrate when we reach ten. We just start over at one.

When day-dreaming occurs and we lose track of the number we are on, we abandon the thoughts that intervened and we count the next exhalation as one or oooooone, depending upon its length. In other words, whenever we discover that we have lost track of the practice, we go back to one.

If we become light-headed or dizzy, we know that we are not breathing naturally.

If we concentrate really hard and enjoy counting the exhalations, we will find ourselves counting twelve, thirteen, and beyond. My record is sixteen. When we realize that we have passed ten, we go back to one.

Passing ten or forgetting what number we were on is of course evidence of lack of mindfulness.

Even if we never make it to ten, or if we go past it, we persist in this practice every day. Master Hakuin taught that when we count our breaths, we are doing what a Buddha does.

Consistent, day-by-day, every day practice is required to learn how to sit in Present Moment Awareness. We soon discover that the days we practice Present Moment Awareness are different from the days we don’t.

This is the way we transcend the tenth dharma realm and rise to the ninth.

We will learn what dharma realms are as we encounter them.

We cultivate happiness by practicing Present Moment Awareness. Mindfulness of the present moment produces happiness. It frees us from the past and the future. It allows us to experience the present, a time few people ever experience, a foreign country few people ever visit.

Dharma Master Hsuan Hua, founder of the Dharma Realm Buddhist Association, teaches in The Ten Dharma Realms Are Not Beyond A Single Thought that happiness must be cultivated so that we do not descend into the lowest of the ten dharma realms.

Sadness, melancholy, and lamentations prevail there. Western scholars translate the tenth dharma realm as “the hell realm” but that is a misleading translation based upon the Judeo-Christian world view. There is no permanent hell in Buddhism, nor can anyone, other than ourselves, send us to such a place. Everything is mind alone.

In the words of Dogen Zenji, quoted more fully below: All of these (the three worlds of desire, form, and beyond form) are the products of our mind alone. The hell worlds belong to the world of desire (the one we live in) and if we find ourselves in the hell worlds, it was our own thoughts that took us there.

There is no vengeful, jealous and wrathful god who will punish us if we don’t believe in it. Even a few Christians understand this ancient Buddhist view. As John Wesley, a contemporary of Master Hakuin but living on the other side of the globe, said in 1740:

But God resteth in his high and holy place; so that to suppose him, of his own mere motion, of his pure will and pleasure, happy as he is, to doom his creatures, whether they will or no, to endless misery, is to impute such cruelty to him, as we cannot impute to the great enemy of God and man. It is to represent the Most High God as more cruel, false, and unjust than the devil!

That quote is taken from a sermon entitled “Free Grace” as found in The Mind of the Bible-Believer.

But there is a need to fear an undisciplined, pleasure-seeking mind that is awash in ignorance. Ignorance is simply the absence of mindfulness.

The practice of Present Moment Awareness is the first step of the two steps required to develop mindfulness and we can’t move on to the second step until we have mastered sitting in Present Moment Awareness.

Master Hsuan Hua says that when we are angry or sad, we are “taking a vacation in hell.” His point is that only we can send ourselves into misery; no third party, no god, sits in judgment on us.

[su_spacer size=”30″]

Master Hsuan Hua, Founder of Dharma Realm Buddhist Association

(1918-1995)

His use of the word “vacation,” is not only humorous but also enlightening: nothing is permanent, not even anger and sadness.

So our first job every morning is to cultivate happiness in order to insulate ourselves from the dharma realm that lacks those qualities.

We cultivate happiness by practicing Present Moment Awareness but happiness alone cannot insulate us from falling into the tenth dharma realm. A church-going, animal-killing, gun-loving, war-monger bigot may be happy. But those who engage in mean-minded activities have no mindfulness.

Thus we understand that the cultivation of happiness requires the cultivation of mindfulness. Acts of cruelty are easy for those who lack mindfulness because they see animals or foreign people as being “others” who are outside their scope of caring.

Nothing is outside the scope of caring for those who are mindful.

This passage is copied from Zen Letters: Teachings Of Yuanwu:

The renowned poet Bo Juyi asked the Bird’s Nest monk: “What is the Way?”

The Bird’s Nest monk said: “Don’t do any evils, do all forms of good.”

Bo Juyi said: “Even a three-year-old could say this.”

The Bird’s Nest monk said: “Though a three-year-old might be able to say it, an eighty-year-old might not be able to carry it out.”

He was called the Bird’s Nest monk because he sat in trees high above the ground when he meditated! He had to be mindful of the present moment to avoid falling.

To understand that happiness and good humor are important parts of spiritual practice is the beginning of wisdom.

As a child, I watched a series of Church of Christ ministers approach their podium every Sunday morning, Sunday night, and Wednesday night, with a solemn, unhappy look. I never saw a smile on a minister’s face as he approached the pulpit, as he preached, or as he left the pulpit.

And the only thing those preachers ever talked about was the need for 100% church attendance and putting money in the collection basket to avoid eternal hellfire.

Many westerners meeting Buddhism for the first time are surprised to learn that the cultivation of joy is one of The Seven Factors Of Enlightenment. Happiness, again, is the foundation upon which all of Buddhism rests. When we make the conscious choice to be happy, and when we persist in daily cultivation, we are seeking the ox and leaving the tenth dharma realm.

The ministers of my childhood were wordlessly teaching just the opposite. Their religion was founded on unhappiness. We were all damned if we didn’t believe that God loved us and he would torture us forever in the most horrible manner imaginable if we didn’t believe he loved us. (That, by the way, is psychological terrorism; we should not subject our kids, or anyone we care for, to such evil teachings).

I shouldn’t use the word “evil.” That’s a religious word. The Buddhist word is “ignorance.” Life is not a battle of good versus evil as the religions teach, nor is it a battle of any kind. But there is ignorance on one hand and wisdom on the other.

The happiness that we deliberately cultivate, however, is a far cry from the joy that is the fourth of the seven factors of enlightenment. That joy is experienced only when we arrive at deep levels of meditation. The Buddha called the fourth factor “unworldy rapture.”

Present Moment Awareness is the indispensible first step to those deep levels of meditation.

By cultivating happiness every day, we create one of the conditions that allows that deep meditation to happen.

Ignorance and delusion, the source of unhappiness and dissatisfaction, are dispelled or rooted out at least in part by deep understanding and contemplation of the Four Noble Truths.

The Buddha identified the three roots of evil as greed, hatred and delusion or ignorance. We run toward things we like (greed), we run away from things we dislike (hatred), and we are ignorant of The Four Noble Truths.

So in addition to leaving the tenth, ninth and eighth dharma realms as we practice the first, second and third steps of Beginning Zen, the first three steps of this course are also designed to help us begin to root out ignorance, hatred/ill will, and greed, in that order.

After we have focused calmly on the present moment for a few minutes, which includes counting our exhalations for as long as we can, we are ready for the second step of our morning practice.

Sitting in Present Moment Awareness, which includes the counting of our exhalations as taught by Zen Master Hakuin, makes us happy and we can say goodbye to the lowest of the dharma realms.

It also helps dissolve the first of The Five Hindrances – sense desire.

It is possible to ignore the remaining steps of this course and to attain (uncover) enlightenment just by practicing Present Moment Awareness each day, morning and evening.

If Present Moment Awareness is practiced to perfection on a daily basis, the remaining steps will unfold naturally. However, only those who have sharp karmic roots, developed from many lifetimes of following the Middle Way, are able to practice Present Moment Awareness with perfection.

The rest of us need to follow our Present Moment Awareness with a second practice. I just (October, 2015) received an email asking: How long should I practice counting the exhalations before moving on to the second practice? Answer: Do the practice and get to know yourself. Your heart will know when it’s time to move on.

But before we move on, there’s one more practice we can use to develop happiness. This one is so well-known you can read about it in the mainstream media: Smile.

And may we never forget Huang Po:

“The arising and the elimination of illusion are both illusory. Illusion is not something rooted in Reality; it exists because of your dualistic thinking. If you will only cease to indulge in opposed concepts such as ‘ordinary’ and “Enlightened,’ illusion will cease of itself.” The Zen Teaching of Huang Po: On the Transmission of Mind

[su_spacer size=”30″]

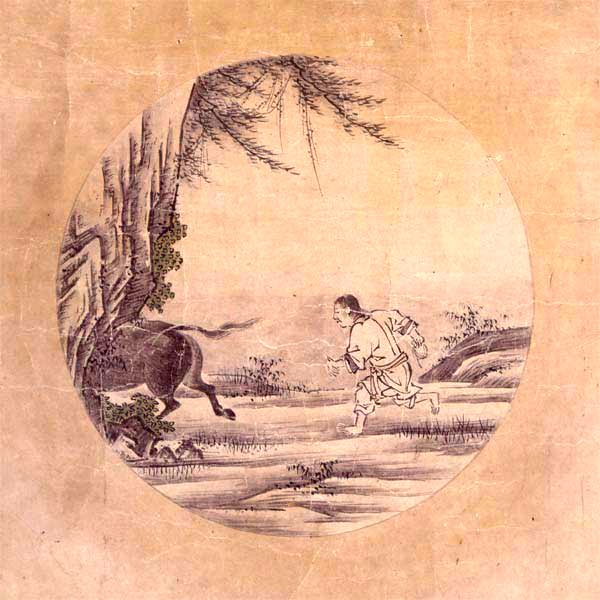

Step 2 – Finding the Footprints

The Ninth Dharma Realm

Along the riverbank under the trees, I discover footprints. Even under the fragrant grass, I see his prints. Deep in remote mountains they are found. These traces can no more be hidden than one’s nose, looking heavenward.

Loving Kindness (metta)

All mankind’s troubles are caused by one single thing, which is their inability to sit quietly in a room.

–Blaise Pascal.

In the commentary for the ox-herding pictures, the second step of Finding the Footprints is referred to as “Finding a path to follow.” Loving Kindness meditation is such a path.

The central practice of this dharma realm is metta, loving kindness meditation. This practice provides the antidote for the ill will that defines this second-from-the-bottom realm, that of the hungry ghosts.

After doing our best to establish Present Moment Awareness, including counting our exhalations as taught by Master Hakuin, we seamlessly transition into a second form of meditation taught by the Theravada school of Buddhism.

This meditation is the perfect meditation to help us climb out of the ninth dharma realm.

Master Hsuan Hua says that dislike and hatred of others (and ill will directed to one’s self as well) causes beings to fall into the ninth dharma realm, known as the realm of hungry ghosts. (They are not hell-dwellers, but their suffering is intense and their spiritual development is below that of animals. Imagine being less aware than a crocodile!)

Most modern people scoff at the notion of a Hungry Ghost dharma realm. It is perhaps best understood when one considers that even animal and plant species are not always clearly defined, i.e., there are animals and plants that blur between species and are difficult to classify. There are even some creatures that can be classified as plants and animals, of course.

The dharma realm of hungry ghosts is thus understood as being a transitional realm between the hell worlds and the dharma realm of animals. The hungry ghosts have developed enough happiness to escape the unhappiness of the “hell” domain but they still are more defiled than animals.

Some teachers say that hungry ghosts are created by excessive greed rather than hate and anger. But Master Hsuan Hua says that excessive greed leads to the dharma realm of animals so we will stick with his teachings. Either way, we don’t want to cultivate hate, anger, or greed. Those are unwholesome states and our job is to cultivate wholesome states.

Therefore, to climb out of the ninth dharma realm, and to ensure that we won’t fall back into it, and to find the footprints of the ox, we practice Loving Kindness (metta) meditation every morning after practicing Present Moment Awareness.

We can Google Loving Kindness meditation and find many different variations of it.

It typically goes something like this:

May I be well, happy, calm, and peaceful.

As we sit in our zazen posture, we repeat that statement (mentally) several times. It helps to reinforce feelings of happiness that we cultivate during the first step of Present Moment Awareness. Then we repeat each of the following statements in the same way:

May all of the members of my family be well, happy, calm, and peaceful.

May all of my relatives be well, happy, calm, and peaceful.

May all of my friends be well, happy, calm, and peaceful.

May all strangers be well, happy, calm, and peaceful.

May the people I dislike be well, happy, calm, and peaceful and may my dislike fade away.

May all beings on the earth be well, happy, calm, and peaceful.

May all beings throughout all of the universes be well, happy, calm, and peaceful.

[su_spacer size=”30″]

(my metta teacher in Clearwater, Florida), wearing his robe which he calls “my tablecloth.”

We sit quietly and still, letting each thought of loving kindness pervade ourselves and the universes. We don’t rush through the practice. By enjoying and savoring each step of the practice, we cultivate patience, the third of The Six Perfections.

By climbing out of the ninth dharma realm, we have found the footprints of the ox and need only one more practice to pull ourselves from the dharma realm that is third from the bottom.

The three dharma realms at the bottom of the ten dharma realms are known in Mahayana Buddhism as the evil dharma realms. With our next practice, step three, we will at least have climbed out of those realms.

Daily metta meditation is of profound importance. We will soon discover its magic.

Sharon Salzberg, a well-known metta meditation teacher even says metta meditation is the only meditation she practices. Her most famous book is Lovingkindness: The Revolutionary Art of Happiness.

[su_spacer size=”30″]

Sharon Salzberg, Co-Founder of the Insight Meditation Society

As we perform our Loving Kindness meditation each morning, dissolving the second hindrance of ill will and insulating ourselves from falling into the realm of hungry ghosts, we can also send to the hell dwellers and the hungry ghosts our wishes that their suffering will soon end so that they, too, can be well, happy, calm and peaceful.

The traditional interpretation of the second stage of the path to enlightenment represented by the ten Ox-herding pictures says that Finding the Footprints (or, to be more accurate, the hoof-prints), is the stage where those few who have persevered and successfully overcome the desire to quit eventually realize that not quitting was the right thing to do.

They have accepted the Buddhadharma and have decided they will continue cultivation, even if they are stuck at the starting line and can’t seem to get past it.

The physical pain of sitting subsides somewhat as we become experienced meditators. We leave behind those who gave up at the seeking the ox stage. We begin to realize that we are all the same person (because we all have the same mind), and thus we understand that we are leaving our old selves behind. Having found the footprints, we are committed to following them until the ox is caught.

Still, no jhana has yet been experienced. The difference between seeking the ox and finding the footprints is just a matter of degree. A resolution to keep practicing matures into a firm commitment to practice every day so that the rowboat of practice does not get swept downstream to the lower dharma realms.

After we have performed our metta meditation, we seamlessly enter into our third practice in order to have a first glimpse of the ox. The third step of our morning practice is the second step of placing mindfulness up front as taught by the Buddha and explained in detail by the Venerable Ajahn Brahm.

We sandwich metta meditation between the two steps of establishing mindfulness because metta meditation is the antidote to ill will and therefore it is the practice that lifts us from the ninth dharma realm. Also, by practicing metta after Present Moment Awareness, we are practicing an enhanced, mindful form of metta.

[su_spacer size=”30″]

Step 3 – First Glimpse of the Ox

The Eighth Dharma Realm

I hear the song of the nightingale. The sun is warm, the wind is mild, willows are green along the shore – Here no Ox can hide! What artist can draw that massive head, those majestic horns?

Silent Present Moment Awareness

The third step on the path is depicted in the ox-herding pictures with the seeker seeing the rear end and tail of the ox as it goes around a corner, i.e., not seeing its head. That’s what the old masters meant by calling this stage the First Glimpse of the Ox.

The central practice of this realm is shikantaza, Silent Present Moment Awareness. It provides the antidote to the greed that causes re-birth in this realm. Millions of people practice shikantaza, which is Japanese for just sitting. The world of Zen has two primary schools, that of shikantaza and that of koans.

When we conclude our loving kindness meditation, we maintain our Present Moment Awareness and transition to Silent Present Moment Awareness. This is how we leave the dharma realm of animals.

After we have sent out boundless loving kindness to all sentient beings in all universes, we simply let that be our last thought. We are finished with thinking and now we are going to let the silence in.

When true silence is attained, we will have our first glimpse of the ox.

Venerable Ajahn Brahm counsels us to make the transition from Present Moment Awareness to Silent Present Moment Awareness by dropping our internal dialog.

Instead of thinking: “I’m beginning to really enjoy this morning meditation practice,” or “Now I’m doing my Loving Kindness meditation,” or “That’s enough lovingkindness, I’m going to do my Silent Present Moment Awareness practice now,” we just conclude our metta meditation and sit without inner commentary.

When a bird chirps, we no longer think: “That was a bird.” We let everything pass without commentary. We exist in the present moment without discursive thought. We drop our thoughts and give our mind a vacation from everything. We let the five senses and the mind just go away into the nothingness, the void from which they came.

Thus by letting go of everything we transition from Present Moment Awareness to Loving Kindness to Silent Present Moment Awareness. We sit in Silent Present Moment Awareness as long as we can.

But how do we actually let go of thought itself? We follow the above instructions of Venerable Ajahn Brahm and the instructions of our Sensei/Roshi, if we have one.

If we have no teacher, we can use an amazing technique commented upon in The Spectrum of Consciousness by Ken Wilbur. The technique was introduced by H. Benoit in The Supreme Doctrine which is the only book I’ve never been able to find on Amazon.

We say to ourself: “Speak! I am listening!”

Our happiness will increase each day and our ill will/dislikes will diminish, as will our greed, as we sit in Silent Present Moment Awareness, waiting for our true self to speak. We may even catch a first glimpse of the ox.

Thoughts stop when we command our self to Speak! We objectify our self in the same way we objectify everything else that we perceive. Thus, when we wait for something to speak, nothing does because the self is waiting for something else to speak.

And the objectified self is the only self we have. It is our own mental creation and nothing is really there. This may seem quite spooky, but it explains what the Buddha meant when he said in The Diamond Sutra that no one has ever been born and no one has ever passed away. Physical bodies come and go, of course, but the birth of a body is not the birth of a Self and the demise of a body cannot therefor be the end of a Self that never was in the first place. This topic is a bit much for Beginning Zen so this famous teaching of the Buddha is continued here.

Enlightenment, called kensho in Japanese, can be shallow or deep. Here is how one person expressed his experience:

“All at once everything became sheer brilliance, and I saw and knew that I am the only One in the whole universe! Yes, I am that only one.”

And another person:

‘All at once the roshi, the room, every single thing disappeared in a dazzling stream of illumination and I felt myself bathed in a delicious, unspeakable delight…For a fleeting eternity I was alone–I alone was…Then the roshi swam into view. Our eyes met and flowed into each other, and we burst out laughing…”

Both of these accounts appear in The Three Pillars Of Zen by Roshi Philip Kapleau.

[su_spacer size=”30″]

Roshi Philip Kapleau, Founder of the Rochester Zen Center

(1912-2004)

These two meditators had caught their first glimpse of the Ox.

And these two meditators had arrived at perhaps the most critical part of the path. The Masters, in the traditional explanation of the ten pictures, tell us that when we catch the first glimpse of the Ox, the experience is so overwhelming that the meditator announces he or she is at one with the Universe and has attained a degree of enlightenment that may very well surpass that of the Buddha.

A few of them will even announce that they are now qualified to teach because no one has ever become as enlightened as they have become.

Venerable Ajahn Brahm makes the interesting observation that those who experience the rapture of the first jhana and the serene happiness of the second jhana usually stop their spiritual evolution at that point. They insist they have seen God or Jesus or whatever or if they are Buddhist they will declare themselves to be enlightened.

These are the people who start religions, not realizing that the First Glimpse of the Ox, other worldly as it may be, is merely the third stage of ten.

However, the First Glimpse of the Ox may fall far short of the first and second jhanas.

So if we persist in practice and get our first glimpse of the ox, it is time to go deeper. The good news is that no further effort is required after the ox has been glimpsed for the first time. Our striving is over because our resistance to practice is over. We want to and will practice Buddhism in all its fullness every day.

We are the happy ones. “This earth where we stand is the pure lotus land and this very body the body of Buddha.” (The concluding line of Master Hakuin’s Chant in Praise of Zazen, which we will encounter in Advanced Zen).

With the passage of time, the bliss wears off and we realize that we have merely glimpsed the Ox for the first time. That is why the Ox-herding pictures were painted in the first place – to let people know that the overwhelming, mind-exploding experience of catching the first glimpse is merely the beginning!

(It’s Shinto, not Buddhist, but it’s pretty)

When the Ox has been glimpsed for the first time, the meditator may have briefly experienced the first and second jhanas. The six senses (the usual five, plus the mind), have shut down, at least for a moment. A person in the first or second jhana never thinks: “This is blissful but my knees are hurting…”

We have risen to the eighth dharma realm, the dharma realm of animals, the dharma realm of greed, and we transcend it by practicing generosity, gratitude, and Silent Present Moment Awareness.

Our Loving Kindness/metta meditation is performed in the present moment. That’s why we practice Present Moment Awareness before practicing metta. We don’t abandon our Present Moment Awareness meditation as we transition into metta nor do we abandon it as we transition into Silent Present Moment Awareness.

We conclude our Silent Present Moment Awareness meditation by reciting the Repentance Gatha (verse):

All unskillful actions performed by me since time immemorial, stemming from greed, anger, and ignorance, arising from body, speech and mind, I now repent having committed.

The version of the Repentance Gatha that I learner years ago began with: All evil deeds committed by me…I guess the new version is better since it seems less religious.

Repentance means little without renunciation. Nazi SS members confessed their mass murders once a week throughout the Holocaust, only to repeat the transgressions the following week. The priests who granted weekly absolution were criticized for doing so but such criticism came too late.

The Repentance Gatha is therefore followed by a vow to renounce “all evil deeds” or “unskillful actions” “so that the repentance has meaning.

We can renounce ill will, greed, animal cruelty/meat-eating, drinking, desires for wealth and fame, etc., and any other activity that conflicts with the precepts.

A monk or nun who leaves home to enter a Buddhist order must renounce family ties and all other worldly ties. Such renunciation, I think, should take place before marriage and children.

The Buddha was married and had a child when he renounced all worldly interests but he lived in a different time. His wife and child were wealthy and even had servants. He also returned to his wife and child upon attaining enlightenment and both of them attained liberation.

This course is for those of us who have no intention to abandon our families and to enter into a Buddhist order as monks or nuns. We lay people can never renounce all worldly things to the same degree as does one who takes the vows of a renunciate for life.

But it is good to associate with such people from time to time and to understand deep renunciation.

Dharma Master Hsuan Hua teaches us to climb out of the third lowest dharma realm, the dharma realm of animals, by overcoming greed. He says that humans fall from the human dharma realm into the animal dharma realm because of greed, i.e., the karmic result of a human life lived with greed is re-birth, as he says, “in fur and horns.” The great master had the comedic touch!

So we repeat the Repentance Gatha at the end of our morning meditation, and several times throughout the day, and vow to reduce our greed. How we practice greed reduction is up to us.

The Repentance Gatha also mentions anger (a form of hatred/ill will; it arises due to things we don’t like) and ignorance.

Recitation of the Repentance Gatha reinforces the work we are doing in the first two steps as well and is thus a nice way to wrap up our practice of Present Moment Awareness, Loving Kindness/metta, and Silent Present Moment Awareness.

We may practice greed reduction by eating just a little less at each meal. Fasting is not a Zen practice so we don’t starve ourselves. But we do think about leaving the dharma realm of animals by teaching ourselves to overcome greed by eating less, by learning to stop before we are stuffed.

If we want to live a lifestyle closer to the lifestyle of a Theravada monk, we can eat one veggie meal per day, before noon. They drink tea in the afternoon and evening.

We cultivate the idea of living a less greedy lifestyle. Our wisdom increases as we understand that the cultivation of generosity can lift us from the animal realm.

Giving, i.e., generosity, the antidote to greed, is the first of the six perfections. So in the first three practices of our morning routine we have climbed from the three evil realms and practiced three of The Six Perfections (generosity, patience, and vigor).

As our happiness/mindfulness/loving kindness increases and our ignorance diminishes day by day with continued practice of these first three steps, we gradually climb out of the evil dharma realms.

But practice without precepts is meaningless, so we also study and follow the precepts. They are introduced in the fifth step of this program, which is the second step of Intermediate Zen.

Silent Present Moment Awareness is the most important meditation practice in all of Buddhism. It is the foundation of all meditation because we establish mindfulness, the first of the Seven Factors of Enlightenment, when we practice Silent Present Moment Awareness.

Without it, the remaining fifteen steps of the Tranquil Wisdom meditation taught by the Buddha is ineffective. And we can’t practice Silent Present Moment Awareness without first practicing Present Moment Awareness.

Of The Five Hindrances to meditation, sense desire is the strongest. When we practice Silent Present Moment Awareness, we overcome, at least temporarily, the most difficult of the hindrances. A practice that establishes mindfulness and overcomes the most powerful of the five hindrances is an indispensable practice.

Sense desire is also the first hindrance of The Five Hindrances and the fourth fetter of The Ten Fetters.

So we have the practice of Silent Present Moment Awareness, also known as shikantaza, to help us cultivate generosity. We can read the late Roshi John Daido Loori’s The Art Of Just Sitting for more information about shikantaza.

Donations to the Tzu Chi organization are an ideal way to practice generosity in a concrete, non-abstract way. Similar to the American Red Cross and the Salvation Army but founded on Buddhist (not military) principles (your money will not be spent on meals for the needy that include the bodies of slaughtered animals), Tzu Chi (Compassionate Relief) is an international relief organization with nominal overhead.

[su_spacer size=”30″]

Master Cheng Yen, founder of Tzu Chi

We can contact Tzu Chi and ask for one of their donation-collecting containers. It is a cylindrical container, pictured below, that serves as a piggy bank. Master Cheng Yen asks that donors place a small amount in coins in the container each day. The containers are emptied each year into a collection vessel during the annual Chinese New Year celebration in Tzu Chi centers which are all over the world.

The Tzu Chi cylinder

If you live far from any Tzu Chi center, you can support their work in the usual way.

We may elect to counter our greed by giving money directly to a homeless person. Or by buying them some food or helping them find a job. Or by sending money to a monk or nun. (They do not accept money directly or personally; it must be sent to their monastery or other practice location for the benefit of the practice center in general).

For more about Tzu Chi, see http://shambhalasun.com/news/?p=54348

But for day-to-day practice of generosity, it’s hard to beat the Tzu Chi way. Perhaps its only drawback is that it encourages such a small amount of generosity each day. But that may be its strongest point!

This concludes our discussion of our Beginning Zen daily practice routine.

The next few pages include background information that explains why we follow these Beginning Zen practices every day.

These concluding pages also provide practical info concerning how to establish a special place for our formal meditation practice, how to sit, and what to expect when visiting a Zen center.

We also include an important advanced Beginning Zen practice that will help us make the transition to Intermediate Zen.

The Five Hindrances

Venerable Ajahn Brahm says that The Five Hindrances are the only hindrances between us and awakening.

1. Sense Desire (people or things we like)

2. Ill will (people or things we don’t like)

3. Sloth or Torpor (sloth refers to sleepiness and torpor refers to mental dullness)

4. Restlessness, anxiety or worry.

5. Doubt. This word “doubt” is better understood when we read the Buddha’s explanation of “doubt.” He said a traveler lost in a desert with no map and no signposts is filled with doubt, not knowing which way is the way to safety.

So doubt is essentially uncertainty, not knowing what to do. We therefore overcome doubt by following the Eightfold path announced by the Buddha.

Hindrances one and two are opposites. We run toward what we like and away from what we don’t. The middle way is to walk down the middle, not chasing sense desires and not running away from everything else.

Hindrances three and four are closely related. Hindrance three arises from too little energy and hindrance four arises from too much. We can’t be so dull that we lose our attentiveness (and mindfulness is attentiveness) but we can’t be racing with hyper mental activity. The middle way is to pay attention but without ego-identification.

That means when a knee starts hurting, instead of thinking “Oh, this is just great. Now my knee is hurting,” instead we note that the knee is hurting, note that it’s just another passing phenomenon, and go back to the practice. We don’t try to ignore or fight the pain, we just accept if with loving kindness as an old friend and return to the practice.

But we don’t make the mistake that Roshi Lou Nordstrom made. When I attended my first Zen sesshin in 1987 at The Bodhi Tree, he told us how in earlier years he attended a sesshin where he sat in full lotus in intense pain, skipping kinhin between sittings, because the guy sitting next to him was skipping the kinhins.

“I let my ego get the best of me,” he explained. “I wanted to prove I was able to endure any pain. When my ligaments snapped, it sounded as if a gun had been fired. I was carried out of the zendo on a stretcher.”

[su_spacer size=”30″]

Lou Nordstrom, Roshi

The Five Hindrances have been masterfully explained by the Venerable Ajann Brahm in Mindfulness, Bliss and Beyond and there is no reason to add anything further to what he has said. Our Zen practice will come to naught if we do not fully understand these Five Hindrances.

The reason that most people sit for years and never awaken is due to their failure to establish mindfulness as the first step in meditation, and failure to overcome the five hindrances.

Obviously, these five hindrances are of paramount importance. As Venerable Ajahn Brahm says, no deep state of meditation can be attained as long as the five hindrances are strong. Only when they are weakened can they be destroyed by deep meditation.

This is no paradox. Although deep meditation alone will destroy the five hindrances, we can enter such deep meditation states when the five hindrances have been weakened by persistent daily practice.

After we have finished a sitting, we review it. What hindrances arose? Did restlessness cause the meditation to end after just a short while? Did sense desire take us to remembering old movie lines and rock ‘n roll songs instead of following the practice?

The Buddha said we need to investigate in this way after a sitting. He said this investigation was the second factor of The Seven Factors of Enlightenment. So let’s not neglect this important step after each sitting.

But most of all, we must remember that it’s the five hindrances that stand between us and enlightenment. So we act accordingly. If we cannot overcome The Five Hindrances, at least temporarily, we have no hope of awakening. And we loosen The Five Hindrances, at least temporarily, when we practice Silent Present Moment Awareness.

[su_spacer size=”30″]

An authentic meditation practice requires a home zendo. Going to a public place of meditation once a week is good but we can do better. Setting up a home zendo for daily practice is a critical step that we shouldn’t skip. This is where we will nurture our authentic Buddhist practice every day, twice a day.

The photo below is a typical home zendo. (“Do,” pronounced with a long “O,” is Japanese for Hall so a zendo is a meditation hall or room). Note that the top shelf holds a Buddha statue; in Asia, it is felt that a Buddha statue should never be used as a casual home decoration. Accordingly, it is displayed only in a meditation room and it is the highest object in the room.

Asian Buddhist custom is also to display live flowers on an altar not just for their beauty but also because they die quickly, thereby serving as a reminder of impermanence. Most Americans prefer to use fake flowers, like those in the photo, to avoid killing flowers needlessly. Even though the artificial flowers seem to be permanent, we can still look upon them as reminders of impermanence.

In this particular arrangement, the main Buddha is flanked by a couple of Guanyin Bodhisattva figures and a couple of smaller Buddhas. There are no particular arrangement requirements. As we visit various zendos and temples, we develop ideas for our home zendo. A table below the shelf can hold candles, a bowl of sand or rice to hold incense sticks, or other suitable objects.

The long strip in the photo between the top shelf and the table is an inexpensive picture of a Thai version of the Buddha on a strip of wood that cost about $15.00; I bought it when visiting a Thai temple in Tampa. The gemstone inlaid picture of the Buddha below that, slightly obscured by a stick of Dragon incense, was purchased for a small amount on eBay.

In the photo below, the large square cushion (zabuton) and the smaller round one atop it (the zafu) are arranged directly in front of the table. A wide selection of zabutons and zafus is also available from Amazon. Most Zen centers use either black or brown/chocolate colors.

[su_spacer size=”30″]

If we don’t want to build a formal miniature zendo like the one pictured, we can at least get a cushion and place it about a foot or so from a wall. When we sit, we face the wall. Try to put the cushion in a special, dedicated place. When we sit, we start our practice right away because we are in our special practice place.

Here’s a pretty incense holder that pays homage to the fact that the Zen sect was created when classic Buddhism from India mixed with China’s indigenous “religion”: Taoism (pronounced with a “D” not a “T.” The tai chi (taiji) symbol is of course Taoist.

The world’s best-smelling (and best-selling) incense is usually associated with Hindu meditation (which has a religious flavor, as distinguished from the Buddha’s rational approach to meditation). However, it’s just incense so it’s OK for Buddhists to use it!

Zen Master Shunryu Suzuki, founder of the San Francisco Zen Center, counsels us to approach Zen practice every day with the mind of a beginner. Thoughts such as: “I’m an advanced student; probably more advanced than anyone I know!” are the thoughts of a decadent, burnt-out practitioner who never got It. We start each sitting fresh, as a beginner.

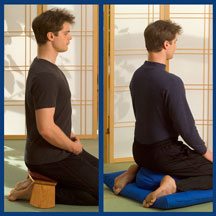

The full lotus is the most anchored of all meditation postures and it is recommended only for the limber. The top posture is the full lotus and the bottom posture is the half lotus. Both postures show the hands in the classic zazen position.

Sitting in a chair requires us to maintain our balance, but if we can get into the full lotus, the balance is easy. Obviously, it’s an advanced yoga position.

It takes most of us a long time to gradually build up to the full lotus.

It’s best for most people to sit in a half lotus position for a long time, alternating between left leg on top or right leg on top, before trying the full lotus.

If we can never get into the full lotus, that’s OK. We can do the half lotus. That is still much more comfortable than the common cross-legged position. The quarter lotus is also an option; it’s a good way to build up to the half lotus.

Other positions are the seiza position (sitting on the feet) and the Burmese position.

Here is a double photo of a practitioner in the seiza position with the aid of a bench on the left and a cushion on the right. The feet are tucked under the bench or positioned on opposite sides of the cushions.

Bench seiza and cushion seiza

Unaided seiza

This practitioner is sitting in classic seiza (sitting on the feet) without bench or zafu cushion. The square mat is a zabuton.

Be careful when buying a seiza bench because the size of the bench depends upon the height of the user. Here is a seiza bench for people who are 5’9″ or less. The lotus flower is also a nice touch as the Buddha is often pictured as sitting atop a lotus flower.

Here is a photo of the Burmese position:

Both feet and both knees are on the mat. Note the hands with the thumbs touching. The left hand fingers overlie the right hand fingers.

I sat for years on a thin, uncushioned meditation mat providing a barrier between me and a floor. After about fifteen years of that, I started sitting at places that used cushions. A typical zendo will have a large square zabuton at each sitting location. A round zafu is placed atop the zabuton, flush with the end furthest from the wall, and the practitioner sits on the zafu with knees resting on the zabuton. The idea is to elevate the rear end a little so that the backbone will be comfortable.

Most people sit just on the front half of the zafu but we can experiment to find how much of the zafu we like to use. We sit cross-legged if we can and use a bench or chair if we can’t. When using a chair, we sit on the front edge with both feet on the floor, keeping our back straight and not using the seat back.

Most Zen centers are equipped with ordinary and ergonomic chairs in addition to zafus, zabutons, and seiza benches.

As a part of this step-by-step guide, we recommend practicing at home alone for quite a while before looking for a Zen center. First of all, we may not live anywhere near a Zen center. Even if we do, the practice is difficult and many people who visit a Zen center early in their practice soon abandon their practice. The sittings are often too lengthy and too numerous for beginners and they give up.

So let’s practice at home until we can sit three rounds of thirty five minutes each, separated by five or six minutes of kinhin between rounds.

The following instructions apply whether we are sitting alone at home or with a group in a Center. A better, more comprehensive and much more authoritative set of instructions on meditation postures is found in The Three Pillars of Zen.

Once seated, we place the right hand on our lap, palm up. Then we place the left hand atop the right hand, also palm up and we let the thumbs touch each other lightly. We keep the thumbs in a vertical plane and put the tongue against the roof of the mouth. With the back and neck straight, the ears should be over the shoulders and the nose facing straight ahead. Some people find it useful to imagine a thread coming straight down from the ceiling or sky with its lowermost end attached to the center of the top of the head. The string is pulling up a little, taking some of the weight of the head away.

We should be seated with the front edge of our zabuton or the front legs of our chair positioned about a foot from a wall. We keep the eyes open just a little but we don’t focus on anything. We hold our head straight, not bending our neck to look down. We look down with our eyes only. If someone waves a hand in front of our eyes, we should be able to see it.

We are not trying to go into a trance and we will not be repeating a mantra until we get blissed out. Zen is not practiced to reach happy, blissful states of transcendence, although such states will appear as a by-product of our meditation. We practice Zen to be here, now. This now and this place is the answer to all questions. Unconditioned Awareness is never some place else at some other time.

When seated on a meditation mat, we are not running around town, burning up gasoline, watching movies, engaging in frivolous chitchat and otherwise generating karma. At last, we are beginning to break free of the karma-generating, imprisoning activities that most people call freedom.

Non-meditators hear of people who sit on meditation mats and say to themselves: Poor things, their life is so boring. The meditator soon learns that the opposite is true; the unexamined life is indeed not worth living. Those who run around thinking they are having a good time are merely fish in an evaporating pool.

Notice the absence of religious sentiment in all of the Buddha’s teachings. No invoking of gods or gurus, secret teachings, no prayer to a deity, no philosophy, no divine revelations, just paying attention to the present moment.

Many people who know nothing or very little about Buddhism have concluded that Buddhism is an atheistic religion. It is neither an atheistic nor theistic religion, however, nor is it a philosophy or a belief system.

Buddhism is the practice of developing wholesome states and abandoning unwholesome states, paying attention to the breath, or working on a koan, and nothing more. If we add anything more to it, we are, as the Chinese say, growing a second head or painting legs on a snake.

When sitting in Loving Kindness meditation, counting breaths, trying to solve a koan, or performing some other teacher-assigned practice, we are doing what a Buddha does; we are not engaging in abstract thought, metaphysical speculation, or wondering what’s for supper. When we catch ourselves immersed in daydreams, or philosophical wanderings, we just drop them and go back to the practice.

How long should we sit and how many times per day? We just do whatever we can. The length of our sittings will increase if we stick with this program. The most important thing for now is to cultivate happiness, get fit, and start a daily home meditation practice in our home zendo.

The Hindu religion expresses the need for repeated spiritual practice by observing how cloth was dyed in the old days. A white cloth would be dipped in yellow dye and the bright yellow cloth would be laid in the sun. After a day of exposure, the cloth would return to almost white, bleached by the sun. The cloth would then be dipped into the dye again, and laid in the sun again. That process would be repeated daily until the bright yellow color would fade less and less until finally it would remain bright yellow even after long exposure to the sun.

Zen practice works the same way. Every day practice adds up. A tenuous, uncertain practice will morph into a rock solid practice.

Even after a few tastes of kensho (an experience of enlightenment that can range from shallow to deep), one must return again and again to the sun of daily life after each round of practice. Even the Buddha continued his meditation practice after his incomprehensible enlightenment.

Comfortable for at least thirty five minutes in the full lotus, the half lotus, or any other formal position? If so, we’re ready to sit with experienced practitioners in a formal zendo.

Most Zen practitioners belong to a sangha and have a teacher. A list of Zen centers in the U.S. can be found at www.buddhanet.net. (Click on World Buddhist Directory in the top line on the home page).

Another good list is found at www.americanzenteachers.org. If we live near any of them, we will have no problem in finding a qualified teacher. Most are called Sensei, Japanese for teacher. A few older Senseis are called Roshi, Japanese for Old Master (but the term “Roshi,” ironically, is not used in Japan).

If you can’t find a Zen center near you, start a center and get listed on buddhanet.net. The easiest way to start a center is to form a Meetup group at meetup.com.

[su_spacer size=”30″]

Roshi Sunya Kjolhede and Roshi Lawson Sachter

Co-Abbots of The Windhorse Zen Community

If our nearest Zen center has no ordained teacher, it’s still better than nothing. Sitting with a lay group is good practice; there is a difference between sitting alone and with a group. If nothing else, group sitting motivates every member of the group because no one wants to be the one who quits! Perhaps that’s a weak reason, but in the early days of a group, it’s true. As the group grows and matures, no one wants to quit because everyone wants to continue practicing together.

[su_spacer size=”30″]

What To Expect When Visiting A Zen Center

We should arrive at least a few minutes before formal sitting begins just to say hello to our fellow practitioners. Just like church. In most cases, we will leave our shoes outside or in a rack in the foyer. Whether we go barefoot or with socks is our choice. At the appointed hour, the Han will begin to play.

The Han is a flat wooden board that is struck by a wooden hammer. The person playing the Han will strike it once loudly, tap it twice lightly, and then repeat a loud, light, loud, light pattern several times and then the last loud will be preceded by two light taps so that the Timer will know that the last loud is about to be sounded. The Timer then brings a pair of wooden clappers together loudly, almost simultaneously with the final loud sounding of the Han.

We walk to our mat during the playing of the Han and get settled down before the Han stops playing. The player of the Han is watching the people in the room so he or she knows when to sound the final loud tap.

In most Zen Centers, the mat of the Timer is assigned to the Timer. We will see a mat with a clock or timer, wooden clappers, and a small hand bell positioned between the mat and the wall. If the Center has a Sensei, a Roshi, or a senior student who is the leader of the group, a mat will be reserved for them as well; it is usually directly beside the Timer’s mat at the entrance to the zendo. All other mats are open; few Centers have assigned seating except during formal retreats when assigned seating is the rule.

Some large Centers also have a mat reserved for each tanto, a senior student charged with wielding the kyosaku (encouragement) stick. Whenever the seating arrangement is somewhat complicated by a number of reserved mats, someone standing by the zendo entrance will direct the sitters toward their individual places.

In a typical Zen center, we will hear the small hand bell ring three times as soon as the Han playing has finished and the wooden clappers have been sounded. The idea is to settle down as the three rings are sounded, spaced a few seconds apart. By the sounding of the last bell, we should be settled into a position that we can hold without movement for at least thirty-five (35) minutes. Some centers sit for twenty (20) and some sit forty (40) minutes or even longer. Call ahead or check the website if visiting an unfamiliar center.

The timer will ring the small hand bell one (1) or two (2) times when the sitting is over, depending upon the Center. In Chinese Ch’an centers, it is common for people to perform a short self massage before rising from the mat. In Japanese Zen centers, everyone performs a palm-to-palm bow while still seated when the bell rings, and rises with no massage.

After arising, we stand on the floor in front of our mat/zabuton, with hands in the gassho (palm-to-palm) position and facing away from the wall. When everyone is standing, the timer rings the small hand bell again, and we all bow to one another at the waist, bending about forty five degrees. We then turn to our left and begin kinhin.

Although the practice can differ between Zen Centers, the typical kinhin is a single file walk at normal speed. Just remember the person in front of us so if we leave the kinhin line to get a drink or go to the bathroom, we will be able to fall in behind that person as we re-enter the kinhin line. The person in front of whom we are stepping will have their eyes down so we lower our right hand and perform a wave as we step in front of them. The kinhin will typically be traveling in a clockwise direction. If in a counterclockwise kinhin, the left hand would be waved.

We place our right thumb inside our right fist. Then we bend our right elbow a little more than ninety degrees so that our right fist is centered on our chest, above our stomach. Then we bend our left arm the same way and cover the right fist with our open left palm.

Some Centers will advise us to place our hands over our stomach so that our elbows are bent ninety degrees with forearms parallel to the floor.

The hands are held in the kinhin position during a fast outdoor kinhin or a slower indoor kinhin. If we need to leave the kinhin, we keep our hands in the kinhin position as we leave and as we return. At night when the sesshin day has ended, we go to our assigned sleeping spot with our hands in the kinhin position. During a work period, even if we are mopping a floor, we return to the kinhin position whenever we can.

As strange as it may seem now, we will come to appreciate the sound of the Han, the wooden clappers, and the hand bell. We will feel right at home, content in the knowledge that we are doing what a Buddha does.

It is perfectly OK to practice counting-the-breath meditation without a teacher. However, we eventually will want to talk to someone who is qualified to discuss our meditation. A Sensei or Roshi may assign a koan or shikantaza (just sitting) instead of a breath practice; however, they will do only what they feel is best for us after they become familiar with our practice.

Zen has several schools in China and Japan but in the U.S., most Zen Centers are either Soto or Rinzai but some Centers blend Soto and Rinzai practices together. The Zen centers of the Roshi Kapleau or the Roshi Aitken lineage, for example, sit facing a wall, Soto style, but most of the practitioners are working on teacher-assigned koans, which is a Rinzai practice.

In the Soto tradition, any one who has practiced consistently for at least ten years is given authority to teach.

In the Rinzai tradition, authority to teach is more difficult to obtain. The student must “pass” a large number of koans, for example, and the process typically takes more than ten years.

As a result, we will find more Soto teachers than Rinzai. Both teach Zen, but a Soto teacher will go easier on us, encouraging us to awaken gradually by maintaining a sustained practice for a long time. A Rinzai teacher will put more pressure on us, encouraging us to wake up Now! A Rinzai teacher will hit us with a stick! (But it won’t hurt).

Both schools have their advantages and disadvantages, but ultimately they are the same. If our practice develops faster by following a Rinzai teacher, we will still maintain a meditation practice for the rest of our life. So it cannot be said that Soto is long, slow, and gradual and Rinzai is short, fast, and abrupt. Both require a lifetime of practice.

[su_spacer size=”30″]

Tekishinjuku International Zendo

We can read what Master Hsuan Hua has to say about the various sects of Buddhism. The magazine of Master Hsuan Hua’s organization (The Dharma Realm Buddhist Association, located near Ukiah, California at The City of Ten Thousand Buddhas) is The Vajra Bodhi Sea. It’s well worth subscribing to.

A period of formal sitting meditation is usually concluded by chanting The Four Bodhisattvic Vows, usually shortened to The Four Vows. A Boddhisattva is a Buddha-to-be. In a typical Zen center, instead of ringing a bell when the last meditation round is over, the lead chanter will begin the chant by intoning:

The Four Vows:

All beings without number…

and then the members of the group join in and conclude the first line and the remaining three lines of the chant:

- I vow to liberate.

- Endless blind passions, I vow to uproot.

- Dharma gates, beyond measure, I vow to penetrate.

- The Great Way of Buddha, I vow to attain.

- The Four Vows are repeated three times.

At the obvious, mundane level, the first line of the chant means what it says: That the chanter, as a Buddha-to-be, will work to spread the Buddhadharma so that all sentient beings can attain Buddhahood.

The great Bodhisattvas have already vowed that they will not enter into Nirvana, the first dharma realm, until the hell worlds are empty and all sentient beings have attained Nirvana. Like a captain of a sinking ship, they work to save themselves last. The Earth Store Bodhisattva is one of those Bodhisattvas.

On a more subtle level, the beings referred to in the first line are our thoughts. To liberate all beings is to stop clinging to our thoughts.

In Buddhism, everything can be understood at an obvious or mundane level, a more intellectual level, and a level that is not renderable in words. It is the continual, mindful recitation of The Four Vows at the conclusion of a formal round of meditation that leads to the beyond-words level.

The other three lines are self-explanatory, at least at the mundane level, but they require hard work. Try uprooting endless blind passions! That’s why Zen is a practice. We can select a passion that we would like to be free of and work on uprooting it. It requires patience, perseverance, and practice.

There is an interesting flow to the four vows:

The vow to liberate all sentient beings obviously begins at home; we surely cannot liberate others before we have liberated ourself.

To liberate all sentient beings including ourself requires no longer clinging to our thoughts, to our endless blind passions that must be uprooted.

And uprooting endless blind passions requires penetration of Dharma gates beyond measure, the study of sutras, repentance…all aimed at the attainment-realization of Buddhahood.

A young monk in his studies came across a passage saying that a certain great master had meditated for eons without attaining Buddhahood. This discouraged him. He went to the Abbot of the monastery and inquired: “Why should I bother to meditate? Why did this great master fail to attain Buddhahood after so many lifetimes of meditation? How can there be any hope for me?”

The master replied: “He did not attain Buddhahood because he did not attain Buddhahood.”

The young monk understood, and happily returned to the meditation mat.

“From the very beginning, all beings are Buddha.”

Buddhahood is inherent in all of us and it is not something we attain. When we vow to attain Buddhahood, the vow is to wake up and experience the Buddhahood that has been there all along. Not to intellectually attain Buddahood, but to experience it.

[su_spacer size=”30″]

Founded by Maizumi Roshi

Maintained by John Daido Loori, Roshi

By cultivating happiness and Loving Kindness, overcoming greed, following the precepts, taking refuge, chanting, reciting the Buddha’s name, studying the sutras, sitting twice a day in meditation, and sharing the Buddhadharma with others, all of which are Dharma gates, we are not causing awakening or enlightenment to occur but we are creating the conditions that allow it to occur.

Repeating the four vows at the conclusion of a formal meditation session is another way of reminding us that Zen practice never ends; we don’t get up from the mat and forget all about zazen. We conclude by vowing to wake up and that keeps the meditation alive as we walk to our cars in the parking lot or head for the subway and re-enter the mundane world.

I once thought it would be funny to tell my Sensei that I had just discovered to my chagrin that I had been reciting The Four Vows incorrectly for years. I then chanted:

All beings without number, I vow to penetrate;

- Endless blind passions, I vow to attain;

- Dharma gates beyond measure, I vow to liberate;

- The great Way of Buddha, I vow to uproot.

- He didn’t think it was funny.

- But he did his best impression of the Queen and said:

- “We are not amused.”

Advanced Beginning Zen

We repeat our morning practices in the evening. We also add a few preliminary practices.

We begin our evening practice by walking in kinhin.

At the beginning of our kinhin, we mentally recite the Three General Resolutions of Zen:

I resolve to avoid evil.

I resolve to do good.

I resolve to liberate all sentient beings.

Reciting these three general resolutions on a daily basis at the beginning of our evening kinhin helps us plant the seeds of happiness that will lift us from the tenth dharma realm and prevent us from returning to it.

[su_spacer size=”30″]

Kinhin at the Victoria Zen Center

Our resolve to liberate all sentient beings puts us in league with the Buddhas of the past, the Buddhas of the present, and the Buddhas of the future. Our job is not to enrich ourselves but to enlighten all sentient beings.

We don’t exist apart from all other sentient beings. It’s impossible to enrich ourselves without also enriching others. That makes us happy to practice; it’s not a selfish thing to do.

Every sentient being receives benefit when a single sentient being practices Beginning Zen.

After reciting the Three General Resolutions at the beginning of kinhin, we concentrate only on the kinhin. We feel the weight on our feet as it shifts back and forth, how it builds up and passes away; we pay attention to the present moment.

In the very early days of practice, it is best to skip the warm-up exercises. After practicing awhile, we can perform the first warm-up exercise, then the second one, etc., until we gradually build up to all of them.

We recommend the Eight Form Moving Meditation taught by Dharma Master Sheng Yen, founder of Dharma Drum Mountain Buddhist Association. We pay attention to the present moment as we perform the Eight Form Moving Meditation after our kinhin. Then we calmly sit for the morning Present Moment Awareness formal meditation.

Similar warm-up exercises are OK, of course, but this particular set comes to us from an awakened Master.

[su_spacer size=”30″]

Master Sheng Yen, Founder of Dharma Drum Mountain Buddhist Association

(1930-2009)

We perform the Eight Form Moving Meditation in a calm frame of mind. We pay calm, light attention to the movements, thereby preparing us for the formal Present Moment Awareness sitting meditation to follow.

This gentle daily warm-up will invigorate us and help us cultivate happiness throughout the day.

Qigong practices can be followed as well for variety. The best book I have found on that subject is authored by Kenneth A. Cohen and is entitled Qigong, The Art and Science of Chinese Energy Healing. I don’t care for the author’s flippant attitude about eating animals but the Qigong exercises are good.

Since happiness/mindfulness is the foundation of all Buddhist practice, it’s our number one job to cultivate it all day, every day. With a strong foundation of happiness, the other nine steps of practicing Zen will easily become second nature.

Vigor is the fourth of The Six Perfections that are cultivated by Buddhas-to-be. So when we seek the ox with morning kinhin, warm-up exercises, and Present Moment Awareness, we not only climb out of the tenth, lowermost dharma realm, we also begin cultivation of an important perfection.

Bodhidharma, an Indian monk, spent nine years meditating in a cave before beginning his career as a teacher at the now famous Shao Lin (Small Forest) monastery in China. He is credited with introducing gong fu (kung fu) to the monks to help them remain physically fit despite long hours of sitting meditation. He is also the twenty-eighth and final Zen patriarch of Indian Zen and the first patriarch of Chinese Zen (Ch’an).

It’s difficult for a physically unfit person to practice zazen. If we are overweight, stiff and inflexible, we need to work on reducing weight and becoming more flexible. That’s why we add warmup exercises as an Advanced Beginning Zen practice.

One reader of this site suggested that I should remove all mention of exercise from the site, saying that sitting on a cushion requires no warming up and no degree of physical fitness.

I replied that the great chess masters exercise like Marines in preparation for their matches. Sitting for hours at a chessboard requires great physical stamina and sitting in a zendo does too.

After the recital of the Three General Resolutions, the kinhin, and the warmup exercises, using the same posture as we did for our morning practice, we repeat our Present Moment Awareness, metta, and Silent Present Moment Awareness practice at night before going to bed. A night sitting is known as a yaza sitting. “Ya” means night and “za” is to sit. Even for beginners, a single daily meditation builds a weak foundation. A night time sitting, just prior to retiring, is helpful.

At the conclusion of our yaza, we recite the four vows:

- All beings without number, I vow to liberate.

- Endless blind passions I vow to uproot.

- Dharma gates beyond measure, I vow to penetrate.

- The great way of Buddha, I vow to attain.

We then stand and perform three prostrations, reciting the following with the first, second, and third prostrations, respectively:

I take refuge in the Buddha, and resolve that with all beings I will understand the Great Way, whereby the Buddha seed may forever thrive;

I take refuge in the Dharma, and resolve that with all beings I will enter deeply into the sutra treasure, whereby my wisdom may grow as vast as the ocean;

I take refuge in the Sangha, and in its wisdom, example, and never failing help, and resolve to live in harmony with all sentient beings.

These are The Three Refuges, the taking of which is traditionally associated with entering the Buddhist path.

As we learn these practices, let’s remember Huang Po and his comments. Here’s one:

“Above all, have no longing to become a future Buddha; your sole concern should be, as thought succeeds thought, to avoid clinging to any of them. Nor may you entertain the least ambition to be a Buddha here and now.” The Zen Teachings of Huang Po: On the Transmission of Mind

By understandijg Huang Po’s point of view, we avoid the error of thinking that we lack something that we need to get, but that we are at least making progress, i.e., that there is an “I” who is advancing toward Buddahood. We are merely tilling the soil, preparing our mind and body for enlightenment without grasping for enlightenment, without wishing we were already there. We are not performing mundane practices in order to become holy; there is no differentiation between the mundane and the holy. The mundane is the holy, the holy is the mundane. We perform our mundane practices with no pretention of performing holy practices.

[su_spacer size=”30″]

Very Advanced Beginning Zen

For very advanced Beginning Zen, we study and perform the practices taught in Present Moment, Wonderful Moment by Thich Nhat Hahn.

Many Buddhist teachers tell us that practicing mindfulness all day long, even when not enaged in formal sitting meditation, is the key to awakening. This book helps us do that by giving us concrete practices we can follow throughout the day.

I realized that Thich Naht Hahn was a truly great Zen master when I visited a Tampa group who said they studied his works and followed his practices.

After a brief period of meditation, the group leader asked everyone to share their thoughts. I will never forget the look of shock on their faces when it was my turn to say something and I said that, in my opinion, they had chosen an excellent teacher because Thich Naht Hahn was one of the greatest living Zen masters.

The leader of the group said:

“Zen master? He’s a Zen master?”

[su_spacer size=”30″]

How To Flunk This Course

I know a few people who meditate but refuse to read the sutras, refuse to follow the precepts, and hold such practices and other Buddhist practices, in contempt. They argue that meditation trumps everything and they can continue to cause misery to other sentient beings because they sit on meditation mats and nothing else matters.

They eat animals, smoke, drink, hunt, fish, own guns, support wars of aggression, and generally behave just like people who have never encountered the Buddhadharma.

That’s how we know that meditation alone is nearly worthless. If meditation has no impact upon our behavior, we are merely wearing out meditation cushions when we sit.

I have even met Zen meditators who don’t want to learn about the jhanas, the Four Foundations of Mindfulness or The Five Hindrances to meditation because they’ve never heard of them and don’t want to fill their minds with too much learning. This is ignorance on steroids.

So let’s practice Zen with an open mind, unafraid to learn, unafraid to practice the full spectrum of Buddhist practices from multiple schools or sects.

Only a pure, wholesome mind can see itself and wake up. A defiled, unwholesome mind can meditate endlessly to no effect.

Zazen, sitting meditation, is important, because it is the eighth fold, samma samadhi, of the eightfold path, but it will not lead to awakening if the meditator ignores the precepts, sutra study, and the other folds of the path.

The Buddha taught that there are three worlds or three main divisions of consciousness.

We live in the bottom one, the one known, confusingly enough, as the six worlds. We have already encountered the bottom three of the six worlds and we encounter the remaining three in steps 4-6 of Intermediate Zen.

This bottom world is also known as the world of sense desire. We cannot transcend it until we experience the jhanas. We don’t reach the jhanas until step 6 of Intermediate Zen.

The jhanas exist only in the second of the three worlds, i.e., the world of form, also known as the fine-material world.

And the immaterial attainments exist only in the highest of the three worlds, the world of formlessness, also known as the world of the immaterial attainments.

We don’t reach the immaterial attainments until step 7 of Intermediate Zen.

Steps 4-7 of Intermediate Zen include the sixteen steps taught by the Buddha.