An authentic meditation practice requires a home zendo. Going to a public place of meditation once a week is good but we can do better. Setting up a home zendo for daily practice is a critical step that should not be skipped. This is where we will nurture our authentic Buddhist practice every day, twice a day.

The photo below is a typical home zendo. (“Do,” pronounced with a long “O,” is Japanese for Hall so a zendo is a meditation hall or room). Note that the top shelf holds a Buddha statue; in Asia, it is felt that a Buddha statue should never be used as a casual home decoration. Accordingly, it is displayed only in a meditation room and it is the highest object in the room.

Asian Buddhist custom is also to display live flowers on an altar not just for their beauty but also because they die quickly, thereby serving as a reminder of impermanence. Most Americans prefer to use fake flowers, like those in the photo, to avoid killing flowers needlessly. Even though the artificial flowers seem to be permanent, we can still look upon them as reminders of impermanence.

In this particular arrangement, the main Buddha is flanked by a couple of Guanyin Bodhisattva figures and a couple of smaller Buddhas. There are no particular arrangement requirements. As you visit various zendos and temples, you will develop ideas for your home zendo. A table below the shelf can hold candles, a bowl of sand or rice to hold incense sticks, or other suitable objects.

The long strip in the photo between the top shelf and the table is an inexpensive picture of a Thai version of the Buddha on a strip of wood that cost about $15.00; I bought it when visiting a Thai temple in Tampa. The gemstone inlaid picture of the Buddha below that, slightly obscured by a stick of Dragon incense, was purchased for a small amount on eBay.

In the photo below, the large square cushion (zabuton) and the smaller round one atop it (the zafu) are arranged directly in front of the table. A wide selection of zabutons and zafus is also available from Amazon. Most Zen centers use either black or brown/chocolate colors. Mine (photo below) was purchased from The Rochester Zen Center.

[su_spacer size=”30″]

If we don’t want to build a formal miniature zendo like the one pictured, we can at least get a cushion and place it about a foot or so from a wall. When we sit, we face the wall. Try to put the cushion in a special, dedicated place. When we sit, we start our practice right away because we are in our special practice place.

The world’s best-smelling (and best-selling) incense is usually associated with Hindu meditation (which has a religious flavor, as distinguished from the Buddha’s rational approach to meditation). However, it’s just incense so it’s OK for Buddhists to use it!

Zen Master Shunryu Suzuki, founder of the San Francisco Zen Center, counsels us to approach Zen practice every day with the mind of a beginner. Thoughts such as: “I’m an advanced student; probably more advanced than anyone I know!” are the thoughts of a decadent, burnt-out practitioner who never got It. Start each sitting fresh, as a beginner.

The full lotus is the most anchored of all meditation postures and it is recommended only for the limber.

This is the full lotus:

This is the half lotus:

Both postures show the hands in the classic zazen position.

Sitting in a chair requires us to maintain our balance, but if we can get into the full lotus, the balance is easy. Obviously, it’s an advanced yoga position.

It takes most of us a long time to gradually build up to the full lotus.

It’s best for most people to sit in a half lotus position for a long time, alternating between left leg on top or right leg on top, before trying the full lotus.

If we can never get into the full lotus, that’s OK. We can do the half lotus. That is still much more comfortable than the common cross-legged position. The quarter lotus is also an option; it’s a good way to build up to the half lotus.

Other positions are the seiza position (sitting on the feet) and the Burmese position.

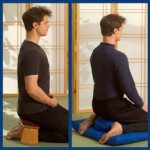

Here is a double photo of a practitioner in the seiza position with the aid of a bench on the left and a cushion on the right. The feet are tucked under the bench or positioned on opposite sides of the cushions.

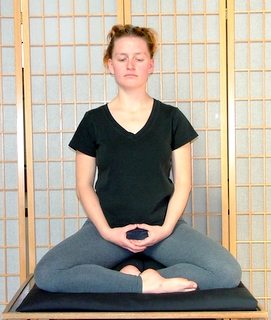

This practitioner is sitting in classic seiza (sitting on the feet) without bench or zafu cushion. The square mat is a zabuton.

Be careful when buying a seiza bench because the size of the bench depends upon the height of the user. Here is a seiza bench for people who are 5’9″ or taller and this one is for people shorter than that.

Here is a photo of the Burmese position:

Both feet and both knees are on the mat. Note the hands with the thumbs touching. The left hand fingers overlie the right hand fingers.

I sat for years on a thin, uncushioned meditation mat providing a barrier between me and a floor. After about fifteen years of that, I started sitting at places that used cushions. A typical zendo will have a large square zabuton at each sitting location. A round zafu is placed atop the zabuton, flush with the end furthest from the wall, and the practitioner sits on the zafu with knees resting on the zabuton. The idea is to elevate the rear end a little so that the backbone will be comfortable.

Most people sit just on the front half of the zafu but we can experiment to find how much of the zafu we like to use. We sit cross-legged if we can and use a bench or chair if we can’t. When using a chair, we sit on the front edge with both feet on the floor, keeping our back straight and not using the seat back.

Most Zen centers are equipped with ordinary and ergonomic chairs in addition to zafus, zabutons, and seiza benches.

As a part of this step-by-step guide, we recommend practicing at home alone for quite a while before looking for a Zen center. First of all, we may not live anywhere near a Zen center. Even if we do, the practice is difficult and many people who visit a Zen center early in their practice soon abandon their practice. The sittings are often too lengthy and too numerous for beginners and they give up.

So let’s practice at home until we can sit three rounds of thirty five minutes each, separated by five or six minutes of kinhin between rounds.

The following instructions apply whether we are sitting alone at home or with a group in a Center. A better, more comprehensive and much more authoritative set of instructions on meditation postures is found in The Three Pillars of Zen.

Once seated, we place the right hand on our lap, palm up. Then we place the left hand atop the right hand, also palm up and we let the thumbs touch each other lightly. We keep the thumbs in a vertical plane and put the tongue against the roof of the mouth. With the back and neck straight, the ears should be over the shoulders and the nose facing straight ahead. Some people find it useful to imagine a thread coming straight down from the ceiling or sky with its lowermost end attached to the center of the top of the head. The string is pulling up a little, taking some of the weight of the head away.

We should be seated with the front edge of our zabuton or the front legs of our chair positioned about a foot from a wall. Keep the eyes open just a little but don’t focus on anything. We hold our head straight, not bending our neck to look down. We look down with our eyes only. If someone waves a hand in front of our eyes, we should be able to see it.

We are not trying to go into a trance and we will not be repeating a mantra until we get blissed out. Zen is not practiced to reach happy, blissful states of transcendence, although such states will appear as a by-product of our meditation. We practice Zen to be here, now. This now and this place is the answer to all questions. Unconditioned Awareness is never some place else at some other time.

When seated on a meditation mat, we are not running around town, burning up gasoline, watching movies, engaging in frivolous chitchat and otherwise generating karma. At last, we are beginning to break free of the karma-generating, imprisoning activities that most people call freedom.

Non-meditators hear of people who sit on meditation mats and say to themselves: Poor things, their life is so boring. The meditator soon learns that the opposite is true; the unexamined life is indeed not worth living. Those who run around thinking they are having a good time are merely fish in an evaporating pool.

Notice the absence of religious sentiment in all of the Buddha’s teachings. No invoking of gods or gurus, secret teachings, no prayer to a deity, no philosophy, no divine revelations, just paying attention to the present moment.

Many people who know nothing or very little about Buddhism have concluded that Buddhism is an atheistic religion. It is neither an atheistic nor theistic religion, however, nor is it a philosophy or a belief system.

Buddhism is the practice of developing wholesome states and abandoning unwholesome states, paying attention to the breath, or working on a koan, and nothing more. If you add anything more to it, you are, as the Chinese say, growing a second head or painting legs on a snake.

When sitting in Loving Kindness meditation, counting breaths, trying to solve a koan, or performing some other teacher-assigned practice, we are doing what a Buddha does; we are not engaging in abstract thought, metaphysical speculation, or wondering what’s for supper. When we catch ourselves immersed in daydreams, or philosophical wanderings, we just drop them and go back to the practice.

How long should we sit and how many times per day? We just do whatever we can. The length of our sittings will increase if we stick with this program. The most important thing for now is to cultivate happiness, get fit, and start a daily home meditation practice in our home zendo.

The Hindu religion expresses the need for repeated spiritual practice by observing how cloth was dyed in the old days. A white cloth would be dipped in yellow dye and the bright yellow cloth would be laid in the sun. After a day of exposure, the cloth would return to almost white, bleached by the sun. The cloth would then be dipped into the dye again, and laid in the sun again. That process would be repeated daily until the bright yellow color would fade less and less until finally it would remain bright yellow even after long exposure to the sun.

Zen practice works the same way. Every day practice adds up. A tenuous, uncertain practice will morph into a rock solid practice.

Even after a few tastes of kensho (an experience of enlightenment that can range from shallow to deep), one must return again and again to the sun of daily life after each round of practice. Even the Buddha continued his meditation practice after his incomprehensible enlightenment.

Comfortable for at least thirty five minutes in the full lotus, the half lotus, or any other formal position? If so, we’re ready to sit with experienced practitioners in a formal zendo.

Most Zen practitioners belong to a sangha and have a teacher. A list of Zen centers in the U.S. can be found at www.buddhanet.net. (Click on World Buddhist Directory in the top line on the home page).

Another good list is found at www.americanzenteachers.org. If you live near any of them, you should have no problem in finding a qualified teacher. Most are called Sensei, Japanese for teacher. A few older Senseis are called Roshi, Japanese for Old Master (but the term “Roshi,” ironically, is not used in Japan).

If you can’t find a Zen center near you, start a center and get listed on buddhanet.net. The easiest way to start a center is to form a Meetup group at meetup.com.

Roshi Sunya Kjolhede and Roshi Lawson Sachter

Co-Abbots of The Windhorse Zen Community

If the Zen center nearest you has no ordained teacher, it’s still better than nothing. Sitting with a lay group is good practice; there is a difference between sitting alone and with a group. If nothing else, group sitting motivates every member of the group because no one wants to be the one who quits! Perhaps that’s a weak reason, but in the early days of a group, it’s true. As the group grows and matures, no one wants to quit because everyone wants to continue practicing together.