Dokusan, or private instruction, provides an opportunity for Zen students to work directly with a teacher in a confidential, face-to-face setting. In the early days of Buddhism in Asia, interactions between Buddhist masters and their students usually occurred in public gatherings of the monastic community, or on spontaneous interchanges during work and other temple activities.

Over the centuries, particularly in Japanese Zen, such interactions became increasingly private and formalized. In time, these private meetings, known by the Japanese term “dokusan,” became an integral part of Zen training. Today in the West, dokusan has become an essential element of practice for many western Zen students, and is especially emphasized in the Rinzai tradition. In Zen retreats, or sesshins, dokusan is usually offered two or three times per day.

An ordained teacher can assign a koan to the student during a dokusan and offer advice and encouragement to the student struggling to “pass” the koan.

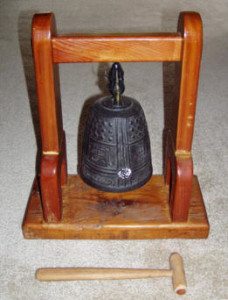

The student bell now owned by the Clear Water Zen Center is pictured above.* When the teacher is ready to start meeting with students, he or she rings a small hand bell and the sesshin monitor responds by sounding the student bell in a crescendo. Most everyone jumps up from their mat and runs to the dokusan room but only the first student to get there enters the room and closes the door. The next two students form a line by the student bell and everyone else returns to their cushion.

Having closed the door, the student may perform a prostration or a bow and then is seated on a mat placed in front of the teacher. If the student and teacher are not well known to each other, the student announces his or her name and what his or her practice is. The student may ask questions concerning practice or may just sit for a few minutes with the teacher, saying nothing. The teacher may test the student or inquire about the student’s practice by asking questions as well.

When the teacher deems the meeting over, he or she rings a small bell. The student stands, takes a step back from the mat, and performs a standing bow which the teacher reciprocates while remaining seated. The student then returns to the zendo, leaving the door open for the next student.

The students who were the second and third students behind the first student will have taken their respective places in a dokusan line which is outside the zendo. When the teacher’s small bell is rung, indicating the end of the first dokusan meeting, the next student strikes the student bell twice so that the teacher will know the next student is coming. The second student enters the dokusan room through the open door, closes it, and follows the same routine as the first.

When those who are still in the zendo hear the two rings of the student bell, one of them can proceed to join the dokusan line because the third student will have moved up to the first place in line, next to the student bell. This procedure is continued until dokusan ends. The monitor indicates the end of the dokusan period by ringing the student bell three times in response to the teacher’s small hand bell.

The routine may vary slightly between different groups. Every sesshin begins with an orientation and procedures are explained at that time.

Beginners enjoy dokusan because it provides a break from long hours of sitting; it feels good to get up during a sitting to join the dokusan line and thereafter to enter the dokusan room. Many students also visit a restroom after a dokusan as well, thereby further lengthening the break before returning to the zendo.

As practice matures, however, the attitude towards dokusan undergoes a seismic shift. The student arises from the mat without letting go of practice, with no thought of taking a break. The student maintains his or her practice and carries it into the dokusan room for the teacher to see.

One of the most amazing sections of The Three Pillars of Zen concerns dokusans. Roshi Kapleau served as the chief court reporter during the Nurenburg war crime trials and as such was proficient in taking shorthand. He also lived in Japan long enough to become fluent in Japanese. Although dokusan is traditionally private, he served as an interpreter for English speakers sitting in dokusan with Roshi Yasutani. With both the permission of the students and the Roshi, he would transcribe, in shorthand, the dokusan conversation as soon as it was over. Those dokusan conversations were, with permission of course, published in The Three Pillars and are the only known records of Roshi/student dokusans that have ever been published.

A dokusan can be less than a minute in length or more than an hour but most are five to fifteen minutes.

Dokusan is associated with sesshin practice and is typically offered several times a day during a sesshin. A student may demonstrate his or her understanding of a koan during dokusan or may just sit in zazen with the teacher. The student may also use the dokusan to ask questions that are relevant to Zen practice.

Although the dokusan room is usually remote from the zendo, I have attended sesshins where I have heard someone scream Mu! at the top of their lungs while in the dokusan room with a teacher. Every scream of Mu! that I have heard sounded forced and insincere to me. I have never been certified as a teacher, but I think even I can distinguish between a heart-felt and a contrived presentation.

And there is no rule that says a student passes Mu! when he or she screams it loudly with selfless abandonment. The teacher is really looking at the student’s eyes, the student’s demeanor; the teacher can tell when a student has seen Mu! or whatever koan the student has been working on.

Whenever my teacher asked me to show Mu! to him, I never felt moved to scream that word with window-rattling force as my fellow students sometimes do. I usually respond to a challenge to show Mu! simply by sitting still. I hear the teacher saying: You are making progress. Keep trying! Then he rings the bell and another dokusan is over.