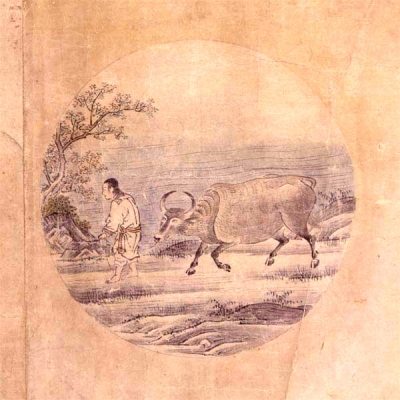

Step Five – Taming the Ox

The Sixth Dharma Realm

The whip and rope are necessary, else he might stray off down some dusty road. Being well trained, he becomes naturally gentle, then, unfettered, he obeys his master.

Mindfulness of Feelings

The sixth dharma realm is the dharma realm. Counting from the bottom up, i.e., ten, nine, eight, seven, six. So we have arrived at our fifth practice.

The central practice of the sixth dharma realm is Mindfulness of Feelings, the second of the four foundations of mindfulness. This practice is the antidote for the five hindrances of sense desire, ill will, sloth and torpor, restlessness and anxiety, and doubt.

By practicing these next four steps, we reach the half-way point of the sixteen steps.

We practice in the human dharma realm. But when we master the four steps of Mindfulness of Feelings, we graduate to the dharma realm of the gods of the six lower dharma realms.

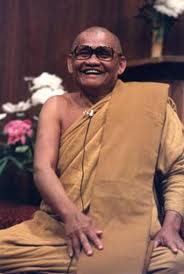

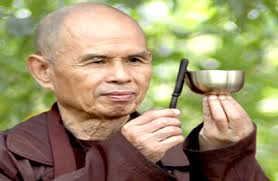

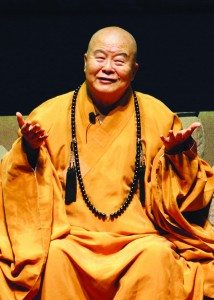

Master Thich Nhat Hanh, founder of Plum Village

These steps can’t be forced to happen for obvious reasons. Only after we have followed every instruction, including the cultivation of happiness, the practice of loving kindness, and so on, can the fourth stage of catching the ox, evolve without effort and without tension into the fifth stage of the Ox-Herding pictures, that of taming the ox.

Step five of sixteen- Awareness of joy

This is how the Buddha describes step 5:

He trains thus: ‘I shall breath in experiencing joy’; He trains thus: ‘I shall breath out experiencing joy.’

When feelings of extreme happiness explode upon us while we are enjoying the breath of the moment, we will know that we have arrived at the fifth step of Tranquil Wisdom meditation. The happiness appears naturally; it can’t be willed. We don’t need to remember what the fifth step is. We can say: OK, I’ve watched the breath of the moment for a long time now – it’s time to get happy, but that won’t work.

The Buddha’s words imply that the joy can be willed. They also imply that the trainee must remember what the fifth step is. So maybe it can be willed by some of us.

We sit with patience and not with greed for the joy that announces we have arrived at the fifth step of our sixteen step meditation.

It is a bubbling, unstable level of delight that naturally evolves into a serene, more stable form of happiness as the sixth step. Ajahn Brahm teaches that this is not yet the joy and happiness of the first two jhanas; it is a herald, though, of what is to come.

Venerable U. Vimalaramsi, however, teaches that the joy of the fifth step is the first jhana. We can say, then, that experience of the first jhana catapults us from the human dharma realm to the dharma realm of the gods of the six worlds.

Meditation is an art, not a science. Thus, both Ajahn Brahm and Venerable U. Vimalaramsi are right; it depends upon the practitioner. For some, the happiness of the fifth step of the Buddha’s Tranquil Wisdom meditation is a mere warmup for the real thing. For others, it’s the first jhana.

Most of us are jolted out of our meditation by the sudden experience of the bliss of the fifth stage, whether it’s the first jhana or not, and the meditation ends abruptly.

With practice, however, we can maintain our calmness and the stage five rapture will settle down into the stage six serenity that lasts a long time.

Step six – Awareness of serenity

We remain aware only of the breath of the moment (the fourth stage) when stage five joy mellows into stage six serenity.

This is the sixth step in the Buddha’s words:

He trains thus: ‘I shall breath in experiencing joy’; He trains thus: ‘I shall breath out experiencing joy.’

Note that he simply substitutes the word “happiness” for the word “joy” as used in the fifth step. Again, this implies that the trainee must remember that happiness follows joy and that the transition from joy to happiness can be willed. For most of us, the joy will naturally settle into happiness and we don’t have to make a conscious decision to make that transition.

Ajahn Brahm calls the breath of one who is experiencing the brief joy of the fifth step and the long-lasting happiness of the sixth step: “the beautiful breath.”

The serenity is stable and long-lasting, unlike the unstable, short-lived rapture of step five. But Ajahn Brahm says this is still not the first jhana.

Venerable U. Vimalaramsi, on the other hand, finds that this is the second jhana, characterized by stability. We are now firmly in the dharma realm of the gods of the six worlds, far above the dharma realm of humans.

Step seven – Awareness of the end of breathing

As the serenity of the sixth step continues, there will come a time, said the Buddha, when the breath is no longer a physical experience. It becomes a mind object, a mental formation.

The meditator is no longer aware of the breath as something that is happening to a living body. From a physical perspective, the breath has become so subtle that it seems to have stopped.

The Buddha describes step seven as follows:

He trains thus: ‘I shall breath in experiencing the mental formation’; He trains thus: ‘I shall breath out experiencing the mental formation.’

We can understand experiencing joy and happiness, but how do we experience “the mental formation”?

The mind is now breathing. As Venerable Ajahn Brahm so eloquently puts it: In the seventh step of the Buddha’s meditation, the beautiful breath is gone, only the beauty remains.

At this point in his wonderful book, Mindfulness, Bliss and Beyond, he shows us an unforgettable connection between this seventh step and Alice in Wonderland/Through the Looking Glass.

When the breath seems to disappear and only the beauty remains and the diversity of consciousness has been brought to this fine point, we still are not finished. As Ajahn Brahms says, there is more bliss to come.

But if we ignore the precepts, as so many modern Japanese, Tibetan and American masters seem to do (I am unaware of any scandal involving a Chinese master), we might as well embrace suffering because we always get what we want. Mick Jagger, who has practiced with Theravada monks in Laos, was wrong when he said we can’t. Yes, I know, it was just a song lyric, but everything is mind alone and we always get what we want.

Step eight – Awareness of equanimity; The Still Forest Pool

After the breath seems to have faded away, we arrive at the eighth step, the Still Forest Pool made famous by the great Thai forest monk Ajahn Chah. We sit by the still forest pool in this eighth step of the Buddha’s Tranquil Wisdom meditation in absolute stillness and tranquility, and wait.

Venerable U. Vimalaramsi teaches that this step eight represents the third jhana, characterized by tranquility. The meditation is named after this step. So we see that the serenity of the sixth step mellows into the minimizing of breath in the seventh step and that mellows even further into tranquility.

The Buddha describes this eighth step as follows:

He trains thus: ‘I shall breathe in tranquilizing the mental formation’; He trains thus: ‘I shall breathe out tranquilizing the mental formation.’

So instead of experiencing the mental formation of the seventh step, we now tranquilize that mental formation. This just means, apparently, that a feeling of tranquility will follow when the breath stops.

Venerable U. Vimalaramsi teaches that step eight is the fourth jhana, the jhana of equanimity. I suppose tranquility matures into equanimity.

If we become excited at our progress, such excitement ends the progress.

As intermediate practitioners, if we can make it to the Still Forest Pool, experiencing the tranquility or equanimity of no breath, we are advanced intermediate practitioners.

If we can make it to the Still Forest Pool, we are in the neighborhood of Nirvana.

If we can’t make it to the Still Forest Pool, we can’t move on and there is no reason to attempt to move on. Ajahn Brahm counsels us that whenever we feel our progress has stopped, we go back and repeat the steps of the meditation that we probably rushed through. Each step has to unfold naturally – we just can’t say: OK, that’s enough happiness, I’m going to start the serenity stage now.

We just sit and watch the meditation unfold all by itself. The mind is unfolding itself and the thing we call our self has nothing to do with it.

When the mind, at its own pace, arrives at the Still Forest Pool, it will stay there awhile. The remaining stages of Tranquil Wisdom meditation will unfold for us just as they did for the Buddha in the year we now call 528 B.C. (The Buddha was most likely born in 563 B.C. and experienced enlightenment at the age of 35).

When absolute tranquility is experienced, the experiencer disappears. Tranquility is, but it doesn’t belong to us.

By taming the ox we arrive at the Still Forest Pool. The mind is tamed. The mind is tranquil. The practitioner has become a meditation master and can catch the ox and tame it. What else could possibly need to be done?

We are just half way through the sixteen steps.

Zazen has become so easy that the temptation to stop practicing is strong. We begin to carefully consider the teachings of the Zen masters that we are perfect and complete, just as we are. We begin to feel that we really are perfect and complete, and that there is no further reason to practice.

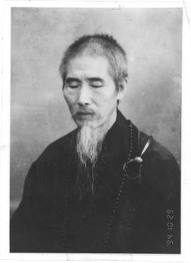

Yasutani Roshi says this is the stage where the meditator must vow to practice for another thirty years.

(1885-1973)

Just as the cultivation of peace and non-struggle, by practicing mindfulness of the body, is the antidote to the fighting and struggling of the asuras of the seventh dharma realm, practicing mindfulness of feelings is the antidote to the untamed mind, the mind subject to and controlled by sense desire, the mind of the sixth dharma realm of humans.

When we practice mindfulness of feelings, the whip and rope are no longer necessary. Our mind becomes well-trained and naturally gentle.

We have reached a point where further progress on the path becomes difficult if we don’t follow the precepts. The next group of four steps, mindfulness of the mind itself, leads to the jhanas according to the understanding of Venerable Ajahn Brahm, and attaining the jhanas while ignoring the precepts is simply impossible.

Nor is it easy to practice present moment awareness without precepts. Counting one’s breaths from one to ten, and repeating that practice, again and again, does not come easily if we are awash in sense desire. Nor can we send out thoughts of loving kindness if we don’t practice acts of loving kindness to all sentient beings in our daily life.

So we pause mid-way through Intermediate Zen to introduce the precepts. Following the precepts helps us practice mindfulness of feelings which is the antidote to the sense desires that dominate the untrained mind of the human dharma realm.

Following the precepts is our insurance against re-birth below the human realm, just as cultivating happiness insures against falling into the hell realms, cutivating good will insures against re-birth in the hungry ghost realm, cultivating generosity insures against re-birth as an animal, and cultivating peace and non-struggle insures against re-birth in the realm of the titans.

Mindfulness: A Practical Guide to Awakening

The Precepts

The sixteen steps of the meditation taught by the Buddha, steps 4-7 of this program, can’t be followed successfully if we ignore the preliminary steps, 1-3, of Beginning Zen, or if we ignore the precepts.

Earlier versions of this website put the precepts earlier in the course but feedback told us that many people never completed the course because they couldn’t get past the section on the precepts.

A common comment was: “If I have to be a vegetarian, I don’t want to be a Buddhist.”

Or: “How dare you put such nonsense on your website? I have been a Buddhist all my life and I love eating meat!” One guy commented that he was happy to learn that I was a vegetarian. “That means there’s more meat for me,” he concluded.

So we now introduce the precepts in the middle of the course even though they should be at the very beginning.

A view of the Tassajara zendo

Precepts are commandments, not suggestions as so many commentators love to say. Whenever a writer says the precepts are mere suggestions, you know they are getting ready to say it’s OK to violate them if you would rather not follow them. A Buddha follows the commandments perfectly and without effort; the rest of us work at it, i.e., practice, until we can do the same. We do not take the precepts flippantly as mere suggestions unworthy of even trying to follow.

However, the Sanskrit word (sila) that is translated as “precepts” means “calming” or “soothing.” Thus, following precepts is soothing, calming. Rejecting the precepts means that one chooses to be unsoothed, uncalmed. Rejecting the precepts means that one chooses not to awaken and to be aggravated.

If we spend many hours in meditation but reject the precepts, we are indistinguishable from those who spend no time in meditation and who also reject the precepts. If meditation has no manifestation in our daily life, it is meditation without wisdom and is utterly worthless. If we live heedlessly, behaving just like a non-meditator, why meditate at all?

The first precept, for most people, is the hardest.

The first five of The Ten Cardinal Precepts are the “lay” precepts; monks and nuns follow hundreds more. They date back to the time of the Buddha and before; the first five, for example, were practiced by the Brahmans long before the advent of the Buddha.

The ancient Buddhist masters tell us that there are ten Dharma Realms. The top four are heavenly realms and the Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, Pratyekabuddhas and Arhats/Arahants of those four realms can never be reborn into the six lower realms (realms ten through five).

Chinese masters teach that keeping the first five precepts ensures that the precept-keeper will at least be reborn in the human dharma realm, which is better than being reborn in the asura realm, which is either one rung down from the human realm or one rung above, depending upon the teacher, or the animal realm which is one rung further down, or the realm of hungry ghosts which is below the animal realm, or the realm of hell dweller which is the lowermost rung, even down from the hungry ghosts.

They further teach that keeping all ten of the precepts ensures rebirth in the Pure Land. The Pure Land is a dharma realm (the fourth dharma realm in the Mahayana order of dharma realms) conducive to spiritual practice, unlike the human realm which sometimes is and sometimes is not. Once the Pure Land has been attained, there can be no further rebirths in the six lower realms and enlightenment is guaranteed. We therefore strive to follow all ten precepts.

When the Virgin Mary became infinitely pure, she gave birth to the Christ. Western theologians can argue at length about whether the conception was immaculate, why God in his infinite power could not just create a Christ from a lump of clay as he did Adam, thereby not requiring the services of Mary, but Buddhists understand that purity produces perfection and that is the true meaning of the Bible story.

Whenever a person practices the Ten Cardinal Precepts to perfection, the Pure Land appears, a Christ appears, a Buddha arises. Different cultures use different words and symbols, but perfection is made manifest when purity is attained and attainment of purity flows from following the Ten Cardinal Precepts.

As enunciated in modern terms by the late Roshi Philip Kapleau, author of The Three Pillars of Zen: Teaching, Practice and Enlightenment and founder of the Rochester Zen Center, here are The Ten Cardinal Precepts:

1. I resolve not to kill, but to cherish all life.

2. I resolve not to take what is not given, but to respect the things of others.

3. I resolve not to engage in improper sexuality, but to lead a life of purity and self-restraint.

4. I resolve not to lie but to speak the truth.

5. I resolve not to cause others to take substances that impair the mind, nor to do so myself, but to keep the mind clear.

6. I resolve not to speak of the faults of others, but to be understanding and sympathetic.

7. I resolve not to praise myself and disparage others, but to overcome my own shortcomings.

8. I resolve not to withhold spiritual or material aid, but to give them freely where needed.

9. I resolve not to indulge in anger, but to exercise restraint.

10. I resolve not to revile the Three Treasures (Buddha, Dharma and Sangha) but to cherish and uphold them.

Taking Precepts at the Zen Community of Oregon

The first precept, the one that drives many people away from Zen practice because they can’t keep it, is a call for not killing.

It doesn’t say not to kill people. It says not to kill, period. See The Lankavatara Sutra.

Again, following a precept results in a calm, soothed mind. The average vegetarian is a little less agitated, a little slower to anger than the average meat-eater. And not even slightly supportive of wars of aggression that the meat-eaters wildly applaud.

Those who do not care about animal life also do not care about human life. They think war is cool and that soldiers are admirable people who “serve” us. But they serve no one but the arms merchants, those who desire the profits that war can generate.

People who eat animals argue that vegetarians also kill carrots, bacteria, etc. and that, therefore, no living being can avoid killing.

True, but there is a difference between killing a sentient being with a central nervous system that can feel pain and killing a carrot that has no central nervous system and that therefore has no means for feeling pain.

Meat-eaters like to say: “You can’t hear the broccoli scream,” as if killing a broccoli plant is the same as killing a cow or a human being. Nice try, but a broccoli plant like a carrot, lacks a central nervous system, lacks nerves, and is not a sentient being.

So the animal killers argue that Buddhism teaches that all things are one, that there are no distinctions between life and death, killing and non-killing, and so on.

They argue that a liberated mind could kill a cow or a human without karmic retribution, by maintaining a pure mind, just like killing an ant as one walks down a sidewalk absorbed in meditation and generating thoughts of goodwill towards all living things.

That is what Japanese Buddhists practiced during the Rape of Nanking (Nanjing). They beheaded people with “the life-giving sword.” They were merely sending the Chinese off to a better world. “We kill them because we love them so much,” said a Japanese commander.

The argument that it is OK to kill people because they are merely being sent to a better world has a major flaw. The same flaw exists in the argument that it is OK to kill animals for food because Buddhists are free of distinctions such as good and bad, right and wrong.

Only an enlightened Buddha has transcended right and wrong. The rest of us have not and therefore we have no license to kill. And no enlightened master chooses to kill people, animals, or insects.

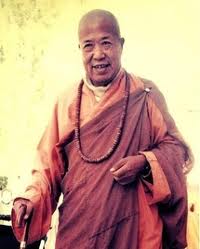

Master Hsing Yun, Founder of Fo Guang Shan (Buddha Light Mountain)

But the Buddha ate meat! Sure; he was a beggar, a mendicant who ate whatever was placed into his bowl. He would not eat the body of an animal if it had been killed for him; he merely accepted whatever leftovers people gave him.

When we walk into a grocery store, we are not beggars who have to go to the meat freezer in the back of the store.

Although it is true that a broccoli plant, like all plants, lacks a central nervous system and thus lacks the ability to feel pain (we hope), nothing in the universe, not even an inanimate object, is dead.

The Buddha taught that there are no two things – the life/death dichotomy, the form/emptiness dichotomy, simply doesn’t exist. That is the meaning of the enigmatic Heart Sutra, perhaps the most famous of the Mahayana texts. (The Heart Sutra is chanted daily in almost every Zen monastery, temple, or meditation practice center in the world.)

How could the life/death dichotomy not exist? The Buddha spent forty five years of his life explaining that only suffering arises and only suffering passes away. This thing we call “living” is just a string of thought moments. There is no thinker of the thoughts.

In the early years of World War II, before U.S. involvement, the Japanese bombed many Chinese cities and towns. Master Hsu Yun (Empty Cloud), who lived to be nearly 120, the teacher of master Hsuan Hua, founder of the Dharma Realm Buddhist Association, lived in one of those towns. Witnesses reported that bombs landing near the Master’s house fell silently, like snow flakes. Not a single one exploded.

(1840-1959)

Even a bomb knows when it is in the presence of a Buddha.

Years later, after founding The City of Ten Thousand Buddhas near Ukiah, California, Master Hsuan Hua visited a student who neglected to tie up his dog. The dog charged up to the Master, and came abruptly to a stop. He bent his front legs and dropped his head, performing a bow.

Even a dog knows when it is in the presence of a Buddha.

When the venerable Dau Sheng spoke the Dharma, dull rocks nodded their heads.

When Zen masters advise us to shun meat and fish eating as a part of our compliance with the first precept, we should at least be as smart as a bomb, a dog, or a dull rock.

For more information, see Vegetarianism, The Food Revolution, and this article from Scientific American.

Being a vegetarian, or better yet, a vegan, is not just a Buddhist stance. All Jains and many Hindu sects have long been vegetarian. Even Christians are slowly coming around. See the Christian Vegetarian Association.

It is about time that some Christians have finally understood that “dominion” implies “stewardship,” and is not a green light to kill.

The second (stealing is to be avoided), third (“improper” sex is wrong) and fourth (don’t tell lies) precepts are self-explanatory and easily understood. But not so easily followed. Being gay, for example, can’t be considered “improper” because it’s an inherent feature and is not consciously chosen, just as heterosexuality is not consciously chosen.

The fifth precept is closely related to the first because it also refers to what we ingest. In the fifth precept we find the Buddha’s instruction to refrain from taking substances that impair the mind such as intoxicating drinks or drugs.

Tea is the traditional drink of Zen, but caffeine can disrupt meditation for people who are sensitive to it. We can find a source of tea that has either been de-caffeinated or better yet, one that is without caffeine from the beginning, like Roibos (red tea from South Africa).

If we drink caffeinated coffee, we can gradually change to decaf and after awhile, drop the coffee and focus on tea, soy, almond, or rice-based milk, fruit juices, and water. We can break our soft drink habit if we have one. If we drink beer, we can switch to a non-alcoholic beer and then gradually cut it out as well so that we can live simply with water, tea, and other non-dairy drinks.

A smoker has a hard time practicing zazen as well; if we smoke, we must stop.

Those who eat animals, drink caffeinated products, smoke, or take drugs other than caffeine and nicotine cannot make it to the end of this program. A pure, undefiled mind cannot reside in a defiled body.

Even those who drink water and tea without caffeine have unstable, wildly veering minds that careen from one excitement to the next; caffeinated minds are even crazier. Those who imbibe caffeinated drinks and soft drinks and booze of any kind are just making a difficult situation worse.

Caffeine and nicotine, like alcohol, are drugs. As the Buddha always said, don’t take anything I say in blind faith; always test it and see for yourself. The Buddha knew that those who take intoxicating drugs were setting up just another roadblock against awakening. So try it and see; as we transition from caffeine, nicotine, alcohol, and animal food, our sitting will become easier.

It may take a few weeks or even months to make the transition, but we can do it.

If we feel that the precepts present an almost insurmountable barrier, let’s consider the heroic example of Tz’u-ming, a tenth century Chinese master.

He would sit and meditate outdoors in the cold of northern China for days on end. When he felt drowsy, he would stab his thigh with a sharp tool known as a gimlet so that he could stay awake to meditate more. For Tz’u-ming, Zen was not a hobby to be casually approached or practiced half-heartedly.

We can follow the example of Tz’u-ming or the example of the average American Zennie who treats Zen practice as just one of the many things he or she likes to do. We can watch American Idol or we can sit in a snowy field and jab ourselves whenever our zeal fades.

Note that all ten of the Precepts include the word “not.” They tell us what not to do. Recognizing that, Roshi Kapleau has added a positive step to each of them (animal food is not served at the Rochester Zen Center).

Sakkaya ditthi is the belief in an independent self. It is listed in the suttas as the first of the ten fetters that bind us to existence in the world of sense-desire. Following the precepts helps to loosen the fetter of sakkaya ditthi.

Ironically, a self-centered desire to get benefits from practice is sakkaya ditthi and a sure guarantee that no benefits will be received. The practice must be approached with a wholesome mind, a relaxed mind that wants only to practice Zen for the daily satisfaction of practicing, not to get a future reward for an illusory self.

The practice is not separate from awakening. As Master Hakuin said, when we sit in meditation, we are doing what a Buddha does.

Sitting in meditation, zazen, is the easiest part of Zen practice. The hard practice comes during the school or work day. The moments between formal sittings, chanting practice, prostrations and the like are when we must learn to carry our Zen practice with us. It is during the moments of our daily life that we must learn to walk in Zen.

And if we are not holding the precepts, we are just wasting our time. Three of the folds of the eightfold path are Right Speech, Right Action, and Right Livelihood. If we ignore the precepts and the moral folds of the eightfold path, the time spent in meditation is just as well spent watching sports on TV.