Step Six – Riding the Ox Home

The Fifth Dharma Realm

Mounting the Ox, slowly I return homeward. The voice of my flute intones through the evening. Measuring with hand-beats the pulsating harmony, I direct the endless rhythm. Whoever hears this melody will join me.

Riding the Ox Home

Mindfulness of the Mind

The fifth dharma realm is the dharma realm of the gods of the six lower realms, often called the six worlds.

The central practice of this realm is the cultivation of the jhanas, the antidote for the desire to remain in the world of desire.

The picture entitled “Riding The Ox Home” is subtitled: “Great joy.” The ox is ours, and we are riding it home. The gods of the six worlds also exist in great joy.

In the traditional explanation of this sixth stage, this stage is so exalted that the meditator is certain that no further zazen is needed. The battle to catch the ox was long ago, and the ox was tamed after a long period of intense post-enlightenment practice. Steps one through five have brought us to the fifth dharma realm, the dharma realm of the gods.

However, these are the gods of the lower six realms, the world of desire which is the third and lowermost world of the three worlds of desire, form, and formlessness.

These are the gods that exhibit all-too human traits like jealousy and anger. The god of the Old Testament (who says men who shave off their beards should be killed, for example) is a god of the fifth dharma realm.

The dharma realm of the gods is far above the human, but it’s still just the fifth dharma realm, the highest of the lower six realms.

The gods of the fifth realm are not infallible, omniscient or perfect. They too, can fall into the lower realms of humans, asuras, animals and worse if they fail to be happy, loving, kind, generous, and upholders of the precepts.

They may endlessly circle the six worlds, i.e., the lower six dharma realms, if they do not practice. Without practice, even a large storehouse of good karma will eventually be used up.

These are the gods who have lifetimes, the ones who become jealous of other gods, the ones who command humans to smite their enemies, and so on. They have great merit but they still belong to the six dharma realms and can fall into any of them, including the lowest, the tenth dharma realm. For example, when the god of the Bible gets so angry that smoke pours from his ears and he starts killing people, he is visiting – taking a vacation in – the evil dharma realms.

Still, when in the fifth dharma realm we feel that we are in the presence of something greater and other than ourselves. We have not yet conquered the feeling of duality, of a self within and a world of others without.

In the ten dharma realms, the leap from the fifth to the fourth is the second biggest one: From the six lower realms to the four heavenly realms. As long as we are in the lower six dharma realms, we can visit all six of them and that is not a good thing. Only the upper four dharma realms are immune from falling into the lower realms, the six worlds.

The three worlds (sense-desire, form and formless) are the three planes of existence and all of them are below Nirvana, which is transcendental and undefinable as a plane of existence.

So even when we reach the dharma realm of these gods, we are still in the lowest of the three worlds and we remain in jeopardy of re-birth in any of the lower six dharma realms.

Instead of one heavenly realm in the bottom six realms (Hakuin’s “six worlds” that we “endlessly circle”), the Pali Canon recites that there are six heavenly realms in the sense-sphere realm.

So who are these unenlightened gods of the Mahayana fifth dharma realm?

From the bottom to the top, with their Theravada dharma realm in parentheses, they are:

The gods under the Four Great Kings (26);

(Recall that Theravada dharma realms 31-27 are the same in number, but in a slightly different order, as the five lower dharma realms (10-6) of the Mahayana dharma realms).

The gods of the Thirty-three (25) (which may explain the name of the famous San-Ju-San Gen Do in Kyoto, san-ju-san meaning “33.” However, there are also said to be 33 gods living atop Mt. Sumeru so the 33 could come from that reference as well);

The Yama gods (24);

The gods of the Tusita heaven (23) (where Bodhisattvas reside before final birth, and thought by some Buddhist scholars to be the heaven of the Bible);

The gods who delight in creating (22); and

The gods who wield power over others’ creations (21).

So the lower six realms of the Mahayana school coincides with the lower eleven realms of the Theravada school, there being an extra five heavens in the latter. But all of those heavens are still in the desire realm and the gods of those realms are subject to re-birth in any of the six or eleven lower realms.

The world of form is realized only through experience of the four jhanas and the world of formlessness is realized only through practice of the four immaterial attainments.

For this reason, we don’t count the experiences of happiness, serenity, tranquility, and equanimity of steps five through eight, respectively, as the four jhanas because we remain in the human dharma realm. It is perhaps best to think of them as heralds of the four jhanas, the jhanas that propel us out of the desire world into the world of form.

Completing the practice of mindfulness of feelings delivers us from the human dharma realm into the realm of the gods of the lower six worlds. We rise above the dharma realm of these gods only upon practicing mindfulness of the mind itself; this is jhana practice.

Steps nine through twelve of the Buddha’s sixteen step meditation are the mindfulness of mind steps.

We experience the body (through the breath) with the four steps of catching the ox, we experience feelings (through joy, serenity, breath cessation and tranquility) with the four steps of taming the ox, and now we experience the mind (and mind alone) with the four steps of riding the ox home.

Riding the Ox Home

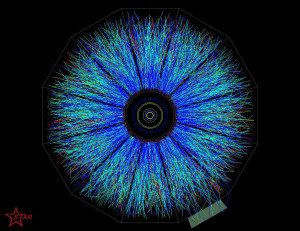

Step nine – Awareness of the nimitta

The Buddha recited the ninth step of Tranquil Wisdom meditation as follows:

He trains thus: ‘I shall breath in experiencing the mind’; He trains thus: ‘I shall breath out experiencing the mind.’

As Venerable Ajahn Chah says, if we sit by A Still Forest Pool with any degree of agitation, the animals won’t come out for a drink. Only when we are as quiet as a pine tree by the pool will the animals come out.

After arriving at the Still Forest Pool, the eighth stage of the Tranquil Wisdom meditation, we sit in absolute equanimity, i.e, our mind is the Still Forest Pool, silent and unmoving. We await the appearance of a nimitta.

Nimitta is the sign of nirvana. We are in the neighborhood of nirvana when it appears. Its appearance is the ninth step.

A nimitta is the mind as seen by the mind, it is the mind experiencing itself. A pure and beautiful mind will experience a pure and beautiful nimitta. If we see a dull, lifeless, ugly nimitta, we know what our mind is.

If a nimitta fails to appear, that means that we have rushed through at least one of the first eight stages.

If we experience no nimitta, we will need to go back and practice, with enhanced patience, the stages we rushed through.

However, the Burmese masters teach that enlightenment may occur even in the absence of a nimitta. I have no idea what they are talking about so we are following the Buddha’s teachings even though it is entirely possible that the Burmese masters have discovered an alternative path that works.

Step ten – Polishing the nimitta

Once the nimitta appears, the tenth step is to “polish” it, in the words of Venerable Ajahn Brahm. His book, Mindfulness, Bliss and Beyond describes how to stop the nimitta from wobbling, i.e., how to strengthen it before moving on to step eleven.

His instructions are quite helpful, because the Buddha’s recital of the tenth step is:

He trains thus: ‘I shall breath in gladdening the mind’; He trains thus: ‘I shall breath out gladdening the mind.’

Ajahn Brahm tells us how to gladden the mind.

Step eleven – Sustaining the nimitta

In step eleven, with the nimitta now stable, we sustain it by the techniques taught by Venerable Ajahn Brahm.

Again, Ajahn Brahm’s specific instructions are helpful. The Buddha’s explanation of the eleventh stage is:

He trains thus: ‘I shall breath in stilling the mind’; He trains thus: ‘I shall breath out stilling the mind.’

Step twelve – Entering into the jhanas

Step twelve, in the Buddha’s words:

He trains thus: ‘I shall breath in liberating the mind’; He trains thus: ‘I shall breath out liberating the mind.’

According to Venerable Ajahn Brahm, once the nimitta is polished and sustained, the four jhanas and the four immaterial attainments may appear as the twelfth step.

Other scholars, however, teach that the four jhanas may be attained in step twelve, but the immaterial attainments are experienced in steps thirteen through sixteen, i.e., the last four steps of the Tranquil Wisdom meditation which we encounter in Step Seven.

Depending upon how well we keep the precepts and how well the nimitta is polished in step ten and made stable in step eleven, we may make it to the first jhana only, to the second jhana only, and so on. No jhana can be skipped, i.e., we cannot experience the third jhana unless we have experienced the first two, and so on.

Just like the joy of the fifth step, the explosion of joy associated with the first jhana usually causes the meditation to end. It takes practice to let the first jhana mature into the second jhana, and so on.

The jhanas transport us from the third world of sense desire to the second world of form, also known as the fine-material world.

In the Theravada teachings, there are sixteen dharma realms in the fine-material world.

The beings of the fine material plane of existence are no longer subject to sense desire and they have left the lower six realms, the desire or sense-sphere realm, never to fall back.

As the name of this collection of realms implies, however, the beings are free of the gross material world but they still have some connection to the material world and have not achieved anuttara samyak sambodhi, total liberation.

Of the sixteen planes of existence, three are associated with the first jhana, three are associated with the second jhana, three are associated with the third jhana, two are associated with the fourth jhana, and the final five are associated with The Pure Land, referred to in the Pali Canon as The Pure Abodes.

More specifically:

Development of the first jhana to an inferior degree leads to rebirth among:

Brahma’s Assembly (20);

Middling development of the first jhana leads to rebirth among:

The Ministers of Brahma (19); and

Superior development of the first jhana leads to rebirth among:

The Maha Brahmas (18).

Thus there are three planes of existence or dharma realms associated with the first jhana.

How can we know if we have attained the first jhana? The Pali Canon mentions four features of the first jhana, as follows:

1. Vittaka which is translated as “thinking”;

2. Vicara which is translated as “examining”;

3. Piti which is translated as “joy, bliss or rapture”; and

4. Sukha which is translated as “happiness.”

Venerable Ajahn Brahm translates vittaka and vicara as subverbal, i.e., non-thinking reactions of the mind.

He teaches that vittaka is the mind’s tendency to flow into a blissful state and vicara is the mind’s tendency to grasp at that blissful state. That grasping weakens the bliss but vittaka lets go of the grasping and the bliss strengthens again.

So if we feel blissful but that bliss seems to “wobble,” as Ajahn Brahm says, that’s the first jhana.

In the same inferior-middling-superior development way, development of the second jhana leads to rebirth among:

The gods of Limited Radiance (17);

The gods of Immeasurable Radiance (16); and

The gods of Streaming Radiance (15).

How can we know if we have attained the second jhana? Well, the first jhana is exhilarating and it doesn’t last long. When the pounding bliss fades away, and only happiness remains, we have entered into the second jhana.

The second jhana is a more stable level of concentration whose primary features are serenity and solidity and it can last for hours; the first jhana is unlikely to last anywhere near that long.

Inferior, middling and superior development of the third jhana leads to rebirth among:

The gods of Limited Glory (14);

The gods of Immeasurable Glory (13); and

The gods of Refulgent Glory (12).

Superior development of the fourth jhana leads to rebirth among:

The gods of Great Fruit (11).

However, if the fourth jhana is developed with a desire for insentient existence (which seems to be a contradiction in terms), then it leads to rebirth among:

The Non-percipient gods (10) “for whom consciousness is temporarily suspended” to quote Bhikkhu Bodhi, author of A Comprehensive Manual of Abhidhamma.

Bhikku Bodhi has also provided the modern translations of the Anguttara Nikaya (numerical discourses of the Budddha, the Mahjjima Nikaya (the middle-length discourses of the Buddha, the Samyutta Nikaya (the connected discourses of the Buddha), and In the Buddha’s Words: An Anthology of the Pali Canon.

As mentioned earlier, the six lower realms of the Mahayana dharma realms are the eleven lower realms in the Theravada understandng because the dharma realms of the gods of the sense sphere is one realm in Mahayana and six realms in Theravada. Thus, in Theravada, dharma realms 31-21 are the realms of sense desire and the lowest of the form realms (Brahma’s Assembly) is thus number 20 of 31.

Bhikkhu Bodhi, author of The Noble Eightfold Path, calls the sixteen realms (20-5) of the fine-material realm the “objective counterparts” of the four jhanas.

But the formless world, the immaterial world (dharma realms 4-1), lies beyond the world of form, and it cannot be experienced until we experience the immaterial attainments.

When I first read about these realms of consciousness, and the creative names by which they are known, my first reaction was to laugh. I thought the gods under the four great kings, the gods of the thirty three, and so on, were the products of someone’s over-active imagination.

I had the same feeling of comic relief when I first read about the levels of consciousness that belong not to the realm of desire but to the realm of form, enterable only through the jhanas.

Brahma’s Assembly, The Ministers of Brahma, the Maha Brahmas, the gods of limited radiance, immeasureable radiance, streaming radiance, limited glory, immeasureable glory, refulgent glory, of great fruit, the non-percipient gods, it was pretty corny.

I have no doubt that someone about 2500 years ago entered into very high levels of bliss and then wrote down his or her experiences.

As the bliss increased, that cultivator would report: I felt like I had entered into Brahma’s Assembly, but then it got even better and I met the Ministers of Brahma, higher still I met the Maha Brahmas. The bliss deepened and I met the gods of limited radiance and they took me to meet the gods of immeasurable radiance and they introduced me to the gods of streaming radiance and after that…

We learn early in our study of Buddhism that the Buddha talked often of the impermanence of things. He taught that those who build their inner happiness on external things are doomed to lose their happiness because nothing lasts forever.

I am sure that a person who enters into the first jhana today, 2500 years after the experience of one early Buddhist was recorded, is unlikely to enter into Brahma’s Assembly, followed by meeting the Ministers of Brahma, and so on.

Brahma’s Assembly and all the other levels of awareness have morphed into something else by now.

A modern person who is ardent and resolute in the cultivation of Zen practices on an unrelenting, daily basis, will certainly enter into blissful states of mind and that bliss will increase in intensity with practice, but it would be nonsensical to believe that these states of bliss with these names will be encountered and that they will appear in the order as recorded by our ancient practitioner.

It’s fun to memorize these states of awareness (I can’t help it) but accepting them as factual, down to their names, would be ludicrous. They were one person’s experience thousands of years ago and we will have our own.

Note that in the Theravada dharma realm countdown, the non-percipient gods reside ten levels of awareness from the top.

Levels 9, 8, 7, 6, and 5 are the highest levels of the realm of form and these levels are the pure abodes of which the Buddha spoke, the realm of the non-returners. They are, from bottom to top:

The Aviha (9);

The Atappa (8);

The Sudassa (7);

The Sudassi (6); and

The Akanittha (5).

The lifetime of the beings in these Pure Abodes increases “significantly in each higher plane.”

We can find in the Pali Canon how far these abodes are from the earth and the specific lifetimes of the inhabitants of each.

No kidding: Some people have actually done the math. They can tell you which Pure Abode is located near the orbit of Jupiter, for example. I hope their humor is intentional.

And if we take such facts literally, we’re nuts. The point is that there are levels of awareness beyond that of the fourth jhana but below the awareness of the immaterial world that lies beyond the world of form.

If the fourth jhana takes our awareness to levels of bliss that some creative ancient cultivator dubbed the gods of great fruit and the non-percipient gods, what meditation practice takes us to the five Pure Abodes, dharma realms 9-5 in the Theravada listing of dharma realms?

Answer: None. The Pure Abodes are like the Christian heaven; we have to die to get there. The five Pure Abodes are where non-returners are reborn. They cannot possibly be re-born into the first world of sense desire but they have not yet attained Nirvana.

As mentioned earlier, keeping all ten precepts to perfection ensures against re-birth in the lower six dharma realms but doesn’t guarantee re-birth in The Pure Land. Keeping all ten precepts will result in a re-birth in the world of form, i.e., the fine-material world, but not necessarily at the high end of that world.

Those who make it the Pure Abodes, where there are no impediments to practice, are guaranteed success. Cultivation continues unabated until all dharma realms are left behind in the Theravada view and Nirvana is attained, or the first dharma realm of Nirvana is attained in the Mahayana reckoning of dharma realms.

But we humans can practice Buddha Name Recitation which the Pure Land teachers say will assure us rebirth in the Pure Land. This is technically not a meditation practice but it probably develops mindfulness and it probably can take a practitioner to the jhanas.

We could make Buddha Name Recitation a practice of the Mahayana sixth dharma realm, the human dharma realm, but since we introduced the precepts at the sixth dharma realm, we have saved Buddha Name Recitation for the Mahayana fifth dharma realm, the realm just above the human dharma realm and the last stop before leaving the third world of desire and entering the second world of form.

Since the fifth dharma realm is the highest of the six lower realms, it makes sense to make Buddha Name Recitation a practice of the unenlightened gods.

Zen and the Pure Land are separate schools in Japan, with Pure Land practitioners greatly outnumbering Zen practitioners, but in China the two schools have merged. Most Ch’an (Zen) practice centers teach Buddha Name Recitation as a Ch’an (Zen) practice.

The Mahayana school does not teach Tranquil Wisdom meditation and thus does not teach cultivation of the jhanas. It has a different approach to the Pure Abodes, referred to in Mahayana texts as the Pure Land.

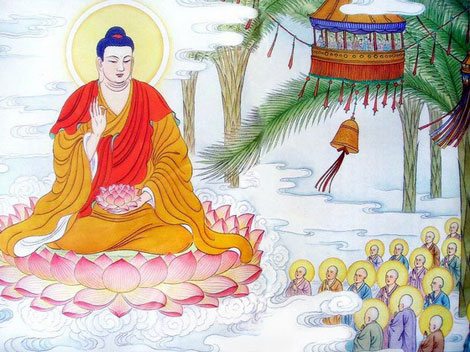

Buddha Name Recitation

The Buddha spoke repeatedly of the Pure Abodes in the Pali Canon and taught that the sentient beings of the Pure Abodes were safely beyond the reach of the desire realm, never again to be reborn as a hell-dweller, a hungry ghost, an animal, a god of strife, a human, or an unenlightened god.

The Mahayana practice is to recite the name of Amitabha Buddha, the Buddha of infinite light and life. We don’t count the number of recitations.

Buddha Name Recitation in Viet Nam

Pure Land practitioners teach that Buddha Name Recitation is the only practice one needs to ensure re-birth in the Land of Ultimate Bliss, i.e., the Pure Land. They recommend recitation practice for people who have trouble with meditation.

With daily Buddha Name Recitation, we assure rebirth in The Pure Land, never again to descend into the lower six realms.

We are not reciting the name of Amitabha Buddha. Amitabha Buddha is reciting Amitabha Buddha.

The sixth fold of the eightfold path is right effort. The Buddha divided right effort into four efforts: 1) Nipping evil/unwholesome thoughts in the bud as they begin to arise; 2) Abandoning evil thoughts that have arisen; 3) Planting wholesome thoughts if our thoughts are neutral; and 4) Nurturing wholesome thoughts that have already arisen.

Buddha Name Recitation practice is an ideal way to practice the four right efforts.

1) Whenever we notice our thoughts taking a negative turn, we recite the name of Amitabha Buddha.

2) If we fail to notice that moment and are already awash in negative thoughts, we drop them by reciting the name of Amitabha Buddha.

3) If we notice that our thoughts are neutral, we recite the name of Amitabha Buddha.

4) If we notice that our thoughts are wholesome, we maintain those wholesome thoughts by reciting the name of Amitabha Buddha.

Amitabha Buddha is not an “other.” We are reciting our own name, remembering who we are.

With whole-hearted and unbroken daily practice of Buddha Name Recitation, we leave the realm of the unenlightened gods and thus leave the six worlds referred to in Master Hakuin’s chant, i.e., the tenth, ninth, eighth, seventh, sixth, and fifth dharma realms, the realms of desire.

Again, the four upper dharma realms are the heavenly dharma realms. The sentient beings in the heavenly dharma realms can never fall back into the six worlds, the bottom six realms.

I once attended a Buddhist Summer Camp in Orlando and after a monk-delivered talk on Buddha Name Recitation, a member of the audience said her practice was to chant One, One, One. She asked the monk if that was a good practice and he said:

“You can chant something that you have developed for your personal use, but you will be chanting alone.”

Buddhism is flourishing in the Republic of China (Taiwan) as well as in the People’s Republic of China (the mainland) so if we chant the Mandarin Namo Amituo Fo, we will not be chanting alone.

Here is an audio file of Namo Amituo Fo in Mandarin Chinese. Very few people chant Namo Amitabha Buddha, the Sanskrit version, but millions chant Namo Amituo Fo.

The fourth dharma realm, that of the Pure Land or the Pure Abodes, is the lowest of the four heavenly realms, but the step from the fifth to the fourth dharma realm is the second biggest step of all because it is the step from the six worlds to the heavenly realms, it is the step of no return. Buddha Name Recitation helps us make that leap.

Moreover, making the effort, every day, to practice Buddha Name Recitation as much as possible by following the four right efforts, samma vayama, helps us to develop the sixth fold of the eightfold path. Whenever we catch ourselves daydreaming or singing a catchy pop tune in our head, we switch to singing Namo Amituo Fo instead. If we are stuck in traffic, we know what to do instead of getting peeved.

Turning to Buddha Name Recitation whenever we can remember to do so gradually clears out the mental cobwebs created by the onslaught of pop culture.

If we practice with diligence, every day, we learn that the dharma realms are real. The Pure Abodes is not a fantasy land.

Amitabha Buddha (Amida Butsu in Japanese)

The Pure Land or the Pure Abodes is the Pure Lotus Land to which Master Hakuin refers in his Chant in Praise of Zazen.

The Pure Land sect, like Zen, is a Mahayana sect and therefore is practiced primarily in the Mahayana countries of China, Japan, Korea, and most of Viet Nam. I don’t know if it’s a part of Tibetan practice or not.

The Buddha mentioned the Pure Land when he discussed the four levels of enlightenment in the Pali canon: the stream winner, the once-returner, the nonreturner and the fully enlightened one.

Venerable Ajahn Brahm in Mindfulness, Bliss and Beyond cites the commentary on the Anguttara Nikaya for his observation that:

“Nonreturners have advanced even further to completely eliminate all desire within the world of the five senses and ill will. Should they not win full enlightenment at the time of their death, then they will arise in the pure abodes (suddhavasa) to attain full enlightenment there. They are never again reborn in the human world.”

This passage from the Pali canon, and many other passages that refer to “the pure abodes” did not inspire the Theravada school to speculate at length about the pure abodes where one may practice until full enlightenment, samyak sambodhi, is attained wihout fear of falling back into the six worlds.

But the Buddha’s multiple references to the Pure Abodes inspired great speculation in the Mahayana school.

Since there is nothing outside us, we make our own world. We take ourselves to the hell worlds, the heavenly realms, the human dharma realm, the animal realm, and so on. As advanced practitioners, we might as well take ourselves to the pure abodes, the Pure Land, the Land of Ultimate Bliss.

The Pure Land is described in the Mahayana sutras as a place that sounds to westerners like the Christian heaven. However, instead of sitting around singing hosannas to the King as in the Christian heaven, the beings in the Land of Ultimate Bliss are cultivating Buddhahood.

Unlike the earth, where cultivation is not always easy, practicing zazen and other forms of cultivation is easy in the Pure Land where everyone is a cultivator.

Pure Land practice requires Faith, Vows, and Practice. The following vow to be reborn in the “Western Pure Land” is recited at the end of a practice period:

“I wish to be reborn in the Western Pure Land, with the nine grades of lotus blossoms as my parents. When the lotuses are in full bloom, I shall see Buddha Amitabha and be enlightened to the Absolute Truth, with non-retrogressing Bodhisattvas as my companions.”

Such a recital strikes us Westerners as bizarre but with repetition it becomes beautiful.

By the way, the term “western” does not refer to the western hemisphere which was of course unknown to easterners when the Pure Land School developed, long before 1492.

Here is my non-scholarly theory of why they called the Pure Land the Western Paradise:

It is known that the ancient Chinese preferred to build their homes facing the south to derive maximum benefit from the sun. Facing south, they knew that the Pacific was to their left and straight ahead so they assumed the Pure Land was to their right. And the west is to the right when facing south.

That’s my theory, but like the lady chanting “One,” I probably hold it alone.

The real reason is that they viewed the setting sun as symbolic of the ending or relinquishment of sense desire or more broadly, the setting of ignorance. And of course the sun sets in the West, in the Western Paradise.

The practice of reciting the name of Amitabha Buddha is reminiscent of the Biblical injunction to “pray without ceasing.” The practice is usually called Buddha Name Recitation or simply Buddha Recitation. English speakers are sometimes encouraged to chant in Sanskrit: “Namo Amitabha Buddha.” The term “namo” looks like the forerunner of the English work “name” but scholars translate it as “praise.”

Amitabha Buddha is not Shakyamuni Buddha, the historical Buddha who announced the Four Noble Truths and taught The Anapanasati Sutta. According to the Mahayana sutras, Amitabha Buddha is a prehistoric Buddha, a Buddha of times that were ancient even during the lifetime of the historical Buddha. Amitabha Buddha vowed to help all sentient beings to awaken if they would but call upon his name.

In Japanese, the Buddha Name Recitation is “Namu Amida Butsu.”

Chinese Buddhists (and others influenced by Buddhism as developed in China) routinely greet and say goodbye to one another with hands palm-to-palm and the words “Amituo Fo.” (“Fo” is Mandarin for the Buddha).

So “Amituo Fo” is used among Chinese Buddhists in the same way as is “Aloha” in Hawaii. A good translation of “Aloha” is: “May you be well, happy, calm and peaceful.”

Worldwide, practitioners of The Pure Land school outnumber Zen practitioners. Some observers conclude that The Pure Land School is for the masses and Zen is for the elite. Au contraire!

Such observations are made by those who recite the Hsin Hsin Ming and still cling to their opinions.

Some Zen writers have said that the Pure Land school violates the basic principle of Buddhism that there are no two things and that we will never find the Buddha outside ourselves. (“If you meet the Buddha on the road, kill him!” means that if you think the Buddha is outside yourself, kill that notion).

Accordingly, some Zen scholars equate Pure Land practice with Christian practice: Calling on a Savior to come and save us is reliance on an “other” whereas Zen teaches self-reliance because there is no other.

In Japan, the practice of Zen is characterized as “jiriki,” meaning “self power,” and the practice of Pure Land is characterized as “tariki,” meaning “other power.” Suffice it to say that even those who think they are reciting the name of someone other than themselves will eventually learn that they have been reciting their own name.

Even though Pure Land practitioners outnumber Zen practitioners, there are still very few serious Pure Land practitioners.

A Pure Land practitioner is not really calling upon an “other” for help. Amitabha Buddha is our true Buddha nature; when we practice Pure Land chanting, we are reciting our true name, remembering our beginningless beginning. It was we who vowed to save all sentient beings. When we chant the name of Amitabha Buddha or Amituo Fo, we are merely calling ourselves to ourselves, remembering our ancient vow. There is no “other” and there is no “out there.”

When we recite the name of the Buddha, the Buddha is reciting the name of the Buddha.

Ch’an Master Hsuan Hua encourages Pure Land practice because it doesn’t conflict with Zen practice in any way. He often assigned to students the koan: Who is reciting the name of the Buddha?

As our Buddha Name Recitation practice matures, we begin to remember who we are.

Master Chin Kung, greeting the Archbishop of Brisbane

Zen as practiced in the States is sometimes called Elite Zen (the exclamation Au Contraire is a joke, stolen from comedian Mark Russell) because its practitioners tend to be middle and upper middle class. The majority of American Zennies, as they call themselves, are college educated and financially secure. Most are heavily into meditation and know little about the Buddhist sutras, the Precepts, and Buddhist practice in general. They pride themselves in being free of the cultural baggage of Asians.

This course includes the cultivation of mindfulness through Present Moment Awareness and Silent Present Moment Awareness, loving kindness meditation, the Repentance Gatha, following the precepts, and taking refuge, subjects seldom if ever discussed in American Zen centers. Very few follow the first precept and many ridicule the very idea of vegetarianism, for example, and threaten to leave the meditation group if the subject ever comes up a second time.

A number of prominent American Zen Centers have been led by sex-crazed Roshis, meat-eating Roshis, alcoholic or drug-taking Roshis, and others who deem themselves to be “above” such “trivial” matters as vegetarianism and a clean lifestyle.

Not only have they failed to repent of their pre-Zen ways, they have never taken the precepts seriously but they do wear a rakusu as if they have. They have no foundation upon which to stand when teaching students.

Starting a meditation practice without precepts and without repentance leads to a Zen practice that is not authentic.

An unrepentant, precept-shunning Zen practice that further ignores the sutras, that considers prostrations a waste of time, and that scoffs at Pure Land practices is equally lacking in authenticity. “Anything goes” Zen is not authentic Zen.

A Pure Land practice also requires authenticity. We cannot just say: “OK, it’s recommended at the Intermediate level so I’ll do it.”

Japanese Zen, as taught in the U.S., does not incorporate Pure Land practice. Chinese Ch’an does and this course obviously tilts toward Chinese Ch’an.

Professor Mark Unno at The Henry David Thoreau Sangha

There are ten great vows that form the foundation of an authentic Pure Land practice. They are recited in the Avatamsaka sutra by Bodhisattva Samantabhadra and form the basis of an authentic Pure Land practice.

The vow to venerate and respect all Buddhas is the first of the ten great vows. Every Buddhist tradition venerates and respects all Buddhas, so this vow is not unique to the Pure Land.

When we perform prostrations, we are bowing to our true selves; we are venerating and respecting all Buddhas. Practicing prostrations, introduced in Advanced Zen, is therefore practicing the first great vow of Pure Land practice.

The second vow grows from the first. A sincere veneration of all Buddhas leads to the vow to praise the Buddhas. This may take the form of mentioning the Buddhadharma to one’s confidants. Buddhists do not, however, proselytize.

The praise may also take the form of Buddha Name Recitation. Thus, when we perform Buddha Name Recitation, we are practicing the second great vow of Bodhisattva Samantabhadra.

If we can recite the name of Amitabha Buddha while performing prostrations, we are simultaneously practicing the first and second vows of the ten great vows.

Responding to a growing veneration for the Buddhas causes the practitioner to praise the Buddhas and to vow to make abundant offerings to them. We do not make abundant offerings just by writing a check payable to a Buddhist organization. Abundant offerings are also made when we practice daily; our practice is our offering. It takes a great vow to follow through and practice these expedient means with diligence.

So our daily practice can represent our making of abundant offerings to the Buddha in fulfillment of the third vow.

We may also make abundant offerings to the Buddhas at our home zendo altar or the altar of our local Zen center in a more mundane way. Flowers, incense, fruits, and the like may be placed with respect on such altars. When we do so, we are practicing the third great vow.

The fourth vow is to repent of misdeeds. So when we follow our Silent Present Moment Awareness with recitation of the Repentance Gatha, we are practicing the fourth great vow.

The fifth vow is to rejoice over the merits and virtues of others. This is mudita, one of the Four Brahma-viharas. This erases envy and the belief in a separate, independent self that causes envy. When a practitioner awakens to the reality that there are no “others,” the merits and virtues of the apparent “others” become a source of delight instead of envy. Our Loving Kindness meditation helps us uphold this vow.

We also practice the fifth vow when we follow the sixth and seventh precepts:

6. “I resolve not to speak of the faults of others, but to be understanding and sympathetic.”

7. “I resolve not to praise myself and disparage others, but to overcome my own shortcomings.”

The sixth vow is to request the Buddha to turn the dharma wheel (to teach the Buddhadharma) and the closely related seventh vow is to request the Buddhas to stay in the world so that the teachings continue.

Fo Guang Shan (Buddha Light Mountain)

The eighth vow is to be reminiscent of the eightfold path, i.e., to follow the Buddha’s path at all times in all situations. The Arhats of the fourth dharma realm have followed the eightfold path to perfection. We recite the eightfold path daily during our prostrations.

The ninth vow is to accommodate and benefit all sentient beings. This is the heart of the Mahayana path. Enlightenment is not pursued for self-gratification because such a pursuit merely strengthens the delusive belief in an independent self. To practice authentic Zen, not just a bare, meditation-only stripped down Zen that ignores the need to follow the precepts, and so on, is to practice for the benefit of all sentient beings.

The practitioner who desires to practice Zen in all of its fullness for the benefit of all sentient beings is a Bodhisattva, a Buddha-to-be, one who has developed the Bodhi Mind.

Recall the first line of The Four Vows: All beings, without number, I vow to liberate. We are making the ninth vow of the Bodhisattva Samantabhadra when we repeat the Four Vows. We are also making the ninth vow when we recite the third line of the Three General Resolutions.

The tenth vow is to transfer all merits and virtues universally. The true Bodhisattva practices Zen in all its fullness and transfers the merit gained thereby to all sentient beings, universally, without discrimination. This is why we end all chanting sessions with the Return of Merit.

All ten of these ten great vows are made daily. We breathe every day, we eat every day, we sleep every day. If we want to wake up, we repeat and practice the ten vows of the Bodhisattva Samantabhadra every day.

Just as the sutras require study, so do The Ten Great Vows of Bodhisattva Samantabhadra. An authentic Zen practice requires that we fulfill these Ten Great Vows.

Those who ignore the fullness of Zen practice are ignorant of the benefits to all sentient beings that would accrue if they would only fulfill the Ten Great Vows.

The following lines may inspire us to perform Buddha Name Recitations:

Speak one sentence less of chatter;

Recite once more the Buddha’s name.

Recite until your false thoughts die,

And your Dharma body will come to life.

In some countries, the practitioners of Buddha Name Recitation have reduced the practice to Christian-like prayer, asking Amitabha Buddha to help them pass school exams, have many children, etc.

The degeneration of Buddha Name Recitation into mere favor-seeking from a god-like entity is probably the reason why it is not practiced in most Japanese-influenced Zen centers in the States.

In centers influenced by Chinese Ch’an, the masters teach that there is no entity out there who is listening to the recitations, no one who will grant favors; again, we are reciting the name of our own original Buddha nature, seeing our face before our parents were born.

We therefore include Buddha Name Recitation as one of the advanced practices that make up our daily Zen practice. Performed with no thought of personal gain, performed as a means for remembering who we are, and performed in the exercise of Right Effort, it adds a valuable dimension to our daily practice.

If we join a Japanese-influenced Zen center where Buddha Name Recitation is not practiced, it is of course OK to respect the teacher’s decision not to include that practice as a part of the center’s practice. We can practice on our own, outside the formal boundaries of the center.

After this lengthy introducton to Pure Land practice, we must recall that it is a practice of the world of form.

The formless world, the immaterial world, lies beyond the world of form, and it can’t be experienced until we experience the immaterial attainments.