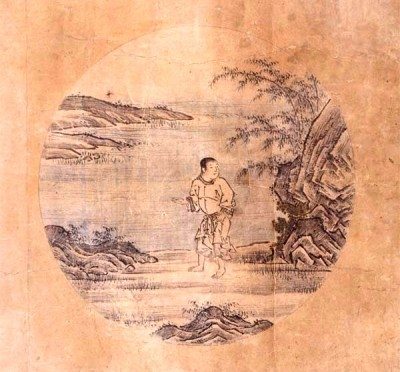

The Ten Ox-Herding Pictures provide a framework for the How To Practice Zen program. Although they were not intended by their artist to be used as a guide, they provide a good outline for building an authentic, daily Zen practice.

The pictures appeared in the twelfth century. They were based on The Sutra of the Ten Stages that was translated into Chinese from Sanskrit in the fifth century. The original Sanskrit was authored about five hundred years before that by Vasubandhu, an Indian patriarch of the Dhyana (Indian)/Ch’an (Chinese)/Zen (Japanese) lineage.

The Ten Stages Sutra appears in its modern form as the 26th chapter of The Avatamsaka Sutra, also known as The Flower Garland Sutra or the Flower Adornment Sutra.

The intent of the Ox-herding pictures and the accompanying text was to depict and explain the stages a Zen practitioner experiences as he or she begins Zen practice, perseveres in the practice, and wakes up to Buddhahood, nirvana.

In other words, the pictures and text are passive in nature, i.e., they represent what happens to a Bodhisattva (a Buddha-to-be) who starts and maintains an authentic Zen practice.

The pictures say nothing about how to start a daily Zen practice, how to develop a full, well-rounded daily Zen practice, and how to sustain one. They passively report what happens when the Zen path is followed with diligence.

In the How To Practice Zen program, the pictures and the accompanying text are used in an active way to teach how to get on and stay on the Zen path.

The Ten Ox-Herding Pictures are entitled:

1. Seeking the Ox

2. Finding the Footprints

3. First Glimpse of the Ox

4. Catching the Ox

5. Taming the Ox

6. Riding the Ox Home

7. Self Alone, Ox Forgotten

8. Both Self and Ox Forgotten

9. Reaching the Source

10. Returning to the Marketplace

The Ox is a metaphor for the enlightened mind. To catch it, we have to discipline our wild, undisciplined monkey mind. The practice of Zen disciplines that monkey mind. We first look for the enlightened mind because we suffer from delusion and perceive it as something separate from ourselves. We then find its footprints, catch a glimpse of it, catch it, tame it, ride it home, forget ourselves, forget the ox as well, break through the Zen barrier, and return to the marketplace as teachers, refraining from entry into Nirvana so that we can benefit all sentient beings.

This is where the Mahayana school diverges from the Theravada. The Arhat overcomes the ten fetters, sees dependent origination, and disappears from the human dharma realm and all other dharma realms as well, according to the Mahayana.

The Bodhisattva remains in the dharma realms to help the sentient beings there. And not just the dharma realms on this planet.

As I child, I asked my Sunday school teacher how people could enjoy heaven with the knowledge that others were in hell. He replied that it was our job to convert everyone to our church and if we failed to do so, at least we tried and it wasn’t our fault that others refused to be converted into the one true church. He had no problem with his belief that a very select few would enjoy eternity while the masses endured eternal agony.

I was just a kid but I realized that my teacher was nuts. But the point of this story is that some Buddhists think something like Church of Christ people – they will try to enlighten everyone but if they fail to do so, they plan to enter Nirvana anyway.

I assume the Arhats do not concern themselves with those they leave behind because they know that suffering is impermanent and that every sentient being will someday enter into Nirvana. They are not mean-minded like my Sunday school teacher who was quite content with the knowledge that unbelievers would burn forever.

Looking for the Ox, finding its footprints, catching a glimpse of it, capturing it, taming it, riding it home, forgetting the desire to become awakened and forgetting the self lead to the Source, to Buddhahood. In the Mahayana tradition, the awakened one then returns to the marketplace, living among the unenlightened and explaining the Buddhadharma (the teachings of the Buddha).

The traditional explanation of the first step, Seeking the Ox, is that a seeker goes through a stage of gathering information, reading about meditation, and eventually trying it. However, the scholars say one has not really sought the Ox until one reaches the stage of frustration or disappointment. When we persevere in the face of hardship, only then are we truly Seeking the Ox.

Thus a person who reads a lot about Zen, tries a few sittings and declares: “That’s not for me,” has not sought the Ox.

In modern times, seeking the Ox for most people takes the form of reading books and visiting Buddhist sites on the web. In ancient times, it meant traveling from monastery to monastery, listening to lectures, looking for a teacher.

Most people today never take that first step. They spend their lives in school, working, raising children, taking vacations, going to the church they grew up in, if any, and getting into hobbies such as spectator sports, dancing, and so on.

If you are one of the few who have been collecting information about Buddhism, you have at least begun to Seek the Ox. A truly unruly mind never looks for the enlightened mind. However, until we practice and persevere through the early discouraging days and weeks and months of pain and disappointment, we haven’t yet begun the search.

Zen: A Simple Path to More Happiness, More Tranquility, and Less Problems