Step Nine – Reaching the Source

The Second Dharma Realm

Too many steps have been taken returning to the root and the source. Better to have been blind and deaf from the beginning! Dwelling in one’s true abode, unconcerned within and without – The river flows tranquilly on and the flowers are red.

The second dharma realm is the dharma realm of the Bodhisattvas, the highest ideal of the Mahayana school.

The central practice is the solving of Zen koans as the antidote to conceit, restlessness, and ignorance (the eighth, ninth, and tenth fetters, respectively).

If we are not familiar with koan practice, we can read Albert Low’s Working with Koans in Zen Buddhism and John Daiso Loori’s Sitting With Koans.

Even though the first dharma realm is the dharma realm of the Buddhas, the Ox-Herding pictures depict the first dharma realm as a Bodhisattva entering the marketplace to teach.

The Theravada ideal of a Buddha who disappears from all dharma realms, never again to be seen or heard from, did not sit well with the Mahayana school. In the Mahayana, the ideal of the Bodhisattva who returns to teach is the highest ideal.

A being of infinite compassion would not disappear, leaving the unenlightened to their sufferings. No compassionate being could enjoy heaven knowing that the hell worlds were occupied.

The Theravada school replies that the Buddha left his teachings behind and thus expressed his infinite compassion.

And that the hell worlds are impermanent and everyone will attain Nirvana someday.

The Zen sect replies that everything is mind alone, i.e., the dharma realms are different levels of awareness. A Buddha can visit the dharma realm of Bodhisattvas.

Reaching or more accurately, returning to the source, occurs when the Zen practitioner is “unconcerned within and without.” According to the commentary that accompanies the ninth picture, all notions of subject and object, self and other, inside and outside, gain and loss, life and death, up and down, beginning and ending, are gone.

Reaching the Source, also known as Breaking Through the Zen Barrier, is the hardest thing an untrained human being can do.

However, we who have honestly followed the first eight steps of this course are no longer untrained.

Jerry Seinfeld tells a story about horses talking to one another after a race. One horse says to another: “After crossing the finish line, I noticed it was the same as the starting line. I could’ve won the race just by staying where I was!”

The traditional commentary on this ninth stage is that when one continues to practice, one breaks through the Zen barrier and realizes that one has returned to the starting line and that one has traveled far just to go nowhere.

It is discouraging at first to learn that when we experience a full-blown, fully matured enlightenment after years of arduous practice, we have merely returned to the starting point. Mountains and rivers are again just mountains and rivers.

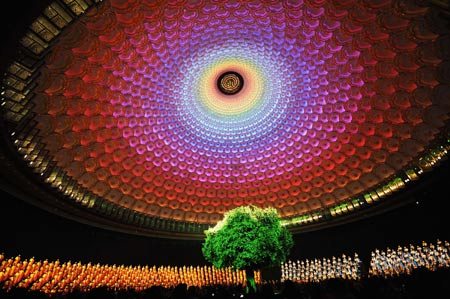

Buddhist temple on the peak of Wolf Hill

Even the verse that accompanies the ninth picture of the ten ox-herding pictures seems to have been written in anger, an emotion that an awakened master would not be expected to exhibit:

Too many steps have been taken returning to the root and the source. Better to have been blind and deaf from the beginning!

But the end of the verse throws more light:

Dwelling in one’s true abode, unconcerned within and without – The river flows tranquilly on and the flowers are red.

(End of verse) This means that the river doesn’t need us to perceive it nor do the flowers. There is no self within to observe the river and the flowers, and no river and flowers without. We have here an affirmation that the dichotomy of subjective/objective doesn’t exist. To see this, we need to return to the source.

No Bodhisattva who is a real Bodhisattva cherishes the idea of an ego-entity, a personality, a being, or a separated individual.

When we have followed the preliminary steps of Beginning Zen and all sixteen steps of tranquil wisdom meditation every day until the practice has become second nature, we have climbed the One Hundred Foot Pole and are ready to leap. Our practice has created the conditions that allow us to break through the barrier, reaching the source.

Too many steps have been taken; that means we have been thinking too much.

The Buddha conveyed in words the sixteen steps that he experienced after first placing mindfulness up front. Obviously, he did not undergo those sixteen steps the way we do – thinking about them, rather than trusting them to flow naturally.

There are no “steps” if we get ourselves out of the way and let the meditation deepen all by itself. The Buddha’s meditation was an analog process but when it is described in words it becomes a digital, step-by-step process.

We work hard to master the sixteen steps and sometimes we do feel that too many steps have been taken. However, we have to practice until we stop thinking about the steps, letting them flow naturally, one after the other without our mental intervention.

But we use our mental intervention, moving from step to step, until the movement flows without us.

When tranquil wisdom meditation becomes effortless, when it meditates itself without our involvement, we are finally ready for Zen practice. It’s time to leap from the One Hundred Foot Pole.

Christmas Humphreys’ commentary on the One Hundred Foot Pole koan explains that climbing to the top of the pole represents the height of thought. That’s what most of us have been doing throughout this program; we are thinking about the steps of the program, and then we think about them some more.

He then explains that leaping from the pole, after we have climbed to its top, represents the existential leap from thought to direct awareness.

Christmas Humphreys, Founder of the London Buddhist Society

(1901-1983)

That’s what it means to break through the Zen barrier; we must go from thought to direct awareness.

We have to go from digital thought to analog direct awareness. From thinking about steps to letting go, and letting go, and letting go until the preliminary steps and the sixteen steps work without us.

We will experience the sixteen steps for the first time as we let go of the sixteen steps.

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

–T.S. Eliot

As professor Timothy Ferris observes in The Whole Shebang, any hack poet could have written the first three lines. Only a genius could have written the fourth.

The ninth step is awakening itself. The tenth step flows naturally from the ninth so this ninth step is the big one.

How can we break through the Zen barrier? And know the place -our mind- for the first time? Zen Master Mumon, referring to working on the koan “Mu,” said:

“Concentrate your whole self with its 360 bones and joints and 84,000 pores, into Mu and making your whole body a solid lump of doubt, day and night, without ceasing, keep digging into it. But don’t take it as “nothingness” or “being” or “non-being.”

“It must be like a red hot iron ball which you have gulped down and which you try to vomit up, but cannot.”

“You must extinguish all delusive thoughts and feelings you have up to the present cherished.”

“Zen means dropping off body and mind,” screamed Ch’an Master Ju-Ching at a monk who had dozed off during zazen.

And from the Diamond Sutra, the most famous exhortation of all:

“Arouse the mind without resting it upon anything.”

Do such exhortations really help? Are we missing something here?

The meaning of “Arouse the mind without resting it upon anything” is well-explained by Roshi Albert Low of the Montreal Zen Center in Zen and the Sutras.

We can meditate before breakfast, before lunch, before dinner, and before bedtime. But if we just sit in quietude, we are not arousing our mind and thus are not arousing our mind without resting it upon anything.

And that is the value of koan practice: It arouses the mind and the koan will not be solved until the aroused mind does not rest upon anything. The “solution” or “answer” to the koan doesn’t rest upon any Buddhist principle. It doesn’t rest upon logic or any other type of thought. It doesn’t rest upon Supreme Oneness because there is no Supreme Oneness out there nor is there one deep within. See Stephen Batchelor’s Confessions of a Buddhist Atheist.

Looking out and looking in both miss the Way. Neither subject nor object will ever be found. Emptiness includes no subject and no object. As we saw in the Hsin Hsin Ming:

If all thought-objects disappear

the thinking subject drops away.

For things are things because of mind,

as mind is mind because of things.

At 2:00 a.m., we can chant Master Hakuin’s Chant In Praise Of Zazen and we can sit until 2:30 a.m.

We can follow the example of Sensei Lawson Sachter, co-abbot of the Windhorse Zen Community; he set his alarm for 2:00 a.m. every night so that he could work on Mu in the middle of the night after having spent the day working on it.

Roshi Philip Kapleau eventually certified that Lawson had seen Mu, and proceeded to assign koan after koan thereafter. He passed all of them and became a fully sanctioned teacher as a dharma heir of Roshi Kapleau. He credits, at least in part, his 2:00 a.m. sittings.

When we catch ourselves daydreaming, we can recite The Ten Cardinal Precepts, we can recite The Four Vows, we can recall all ten of the Ten Great Vows of Bodhisattva Samantabhadra, or we can perform Buddha Name Recitations. That avoids wasting time on frivolity. As Roshi Kapleau said:

“Great is the matter of birth and death.

Life slips quickly by.

Time waits for no one.

Wake up! Wake up!

Don’t waste a moment.”

But really, how does one not waste a moment?

When feelings of lethargy arise, when we just want to lie down and take a snooze, we can follow Ajahn Brahm’s advice and do exactly that. But when we are rested, we can hit the meditation mat.

After all, the last words of the Buddha were:

“All compounded things decay. Work out your salvation with diligence.”

But how is that done?

Venerable Ajahn Brahm teaches that many mind objects may be contemplated after the meditator has emerged from the jhanas because the mind has acquired what he calls “super power mindfulness.”

Of course his use of the term “super power” jokingly refers to the super powers of various cartoon characters, but the idea of mindfulness being so strong that it is super powerful is a perceptive observation.

A Zen koan is a mind object. (Until it isn’t)!

Therefore, super power mindfulness can be used to work on a Zen koan that has been assigned by a teacher. After struggling with koans for years, we can develop super power mindfulness by following the Buddha’s sixteen steps and at last finally demonstrate to our teacher that the koan has been solved.

Although this website is called How To Practice Zen, until now we have obviously been learning primarily about Tranquil Wisdom meditation as taught in the Pali Canon. But we have been leading up to the Zen practiced by the Rinzai sect.

Harnessing the power of super power mindfulness is the key to cracking open a Zen koan. Without it, a Zen student can struggle a lifetime with koans and never open the gateless gate. With it, the koans are seen and the gate opens.

Tranquil Wisdom meditation provides the super power mindfulness required for koan penetration.

We will never hear that observation from a Theravada teacher because they ignore koans.

We will never hear that observation from a Zen teacher because they ignore Tranquil Wisdom meditation.

Most Zen students are assigned counting the breath as taught by Master Hakuin as their first practice, and then they are given a koan to solve.

No Zen teacher tells a Zen student to develop super power mindfulness as taught by the Buddha in the Anapanasati Sutta for koan penetration. If you are a Zen teacher who has taught tranquil wisdom meditation to students to develop super power mindfulness for the purpose of penetrating a Zen koan, (before learning that technique here, of course) please Contact Us.

The Buddha, Bhante U. Vimalaramsi, and Venerable Ajahn Brahm have given us the key to super power mindfulness. That’s what we have when we finish the sixteen steps.

An authentic Rinzai Zen practice can now begin. We practice the preliminary steps to put mindfulness up front and then we practice the sixteen steps that lead to super power mindfulness.

We then turn our super power mindfulness onto our teacher-assigned koan. We demonstrate that koan and the teacher gives us another one and we demonstrate it as well.

Over and over, the koans keep coming and we show every one of them to our teacher by subjecting the koan to the super power mindfulness generated by Tranquil Wisdom meditation.

Failure to penetrate a koan then is understood as simply practicing without super power mindfulness.

We reach the source by penetrating every koan our teacher assigns to us.

And when that happens, we become a dharma heir of our teacher and that takes us to the first dharma realm. A certified Zen teacher who receives full dharma transmission from a certified Zen teacher who received full dharma transmission, and so on, joins the line of mind-to-mind dharma transmission that began with the Buddha Shakyamuni.

Our practice never ends. We carry it into the marketplace, into the hustle and bustle of daily life.

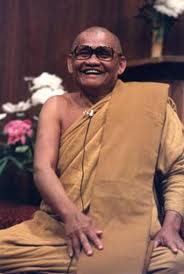

In A Still Forest Pool, the authors relate a story about the time when Venerable Ajahn Chah of Thailand was approached by a monk who had spent three years in his monastery.

The monk announced that he would be moving on to another monastery because he wanted to practice under an enlightened master. He told Ajahn Chah that he noticed that on some days the master was cheerful, friendly, and soft, yet on other days he would seem hard and unapproachable. His moods seemed to swing up and down, just like those of a normal person.

“How can I obtain enlightenment when my master himself is not enlightened?” the monk asked.

Ajahn Chah smiled.

“See, there you go again,” said the monk, “acting like you’re pleased that I’m leaving.”

“I’m smiling because I am happy,” said the great master. “This is a wonderful day. Today, after wasting three years, you will finally begin your spiritual practice.”

“You have been watching me, looking for the Buddha.”

“Today you have finally learned that you will never find the Buddha outside yourself.”

The monk performed a prostration and returned to his meditation hut. He understood the Buddha Dharma for the first time.

(1918-1992)

Many people wonder about the meaning of: “If you meet the Buddha on the road, kill him.” It means to kill the notion that the Buddha is outside ourselves; if we think we have found the Buddha outside ourselves, we must drop that thought.

We will never find the Buddha on the road, in a book, or on a website. However, if we work hard and diligently follow the steps of this course, including working with a sanctioned teacher, we will find the Buddha.

But the Buddha is emptiness, the Buddha has no self. Zen practice does not purify a self so that it can become a Buddha. Zen practice brings suffering to an end because only a self can suffer.

Super power mindfulness, the result of following the Buddha’s sixteen step Tranquil Meditation, penetrates koans.

We do not look for a savior outside ourselves nor do we seek a kingdom of heaven within ourselves. We awaken to no-self.

The Ox-Herding Pictures follow a cycle from beginning to end, and the end is the beginning. Who seeks the Ox? Who finds the footprints?

Our inherent Buddha nature seeks the Ox and finds the footprints.

But what is the point of realizing Buddhahood? It is not to selfishly acquire freedom from suffering for oneself because there is no independent self.

The point of attaining Buddhahood is to relieve the suffering of all sentient beings. This is done in our daily life by following The Precepts and maintaining our daily practices with diligence.

An authentic Zen practice creates super power mindfulness and that super power mindfulness mends the rip in reality created by delusion, knitting reality back to its oneness.

Beginnings and endings return to their original beginningless beginning and endless ending, the dharma realm of the Buddhas, free of mortal thoughts.

We have started a Zen practice, but we have to sustain it every day. It’s easy to slide back, like an upstream-bound rowboat drifting downstream when the oars are not used.

Upon harnessing super power mindfulness to penetrate koans, the bottom will drop out of the bucket. As Roshi Phillip Kapleau said, he felt like a fish swimming in cool, clear water after having been stuck in glue.

We will understand, for the first time, Yuanwu’s words, found in Zen Letters:

“Fundamentally, the Path is wordless and the Truth is birthless. Wordless words are used to reveal the birthless Truth. There is no second thing. As soon as you try to pursue and catch hold of the wordless Path and the birthless Truth, you have already stumbled past it.”

What does: “There is no second thing” mean? It means that nothing has ever happened.

This is the secret that Zen practice reveals: There are no secrets because everything is obvious. Nirvana is openly shown to our eyes. If we use our discriminating, thinking mind, the mind that divides everything into parts, then we make it hidden and non-obvious. We do that to ourselves; no one is doing it to us.

Having eaten the forbidden fruit, we now believe that we are independent entities having a birth date when we entered into existence and that we will have a death date when we exit existence. We have fallen from the garden of wisdom into the badlands of ignorance. We have to empty the cup of nonsense, of delusion, and super power mindfulness does exactly that.

There are no seams in a stupa. There are no beginnings nor are there endings. As the third patriarch of Zen says in the Hsin Hsin Ming, there is no yesterday, no tomorrow, no today. Reality is indivisible and completely empty; we can divide it in our minds, but it is our mind that gets divided, not emptiness. It’s like time; we say it is limited but it is the delusion we call “us” that is limited. Time is inexhaustible; use up quadrillions of years, and nothing has been used up.

Our Buddha nature is the same way. Nothing is there to get used up.

The Chaukhandi stupa, Sarnath, India

Judging, dividing good from evil, today from tomorrow, life from death, creates the thinking mind, the self that is separate from the whole, the self that expels itself from the garden, the self that is a collection of mortal thoughts.

And mortal thoughts are the opposite of super power mindfulness just as ignorance is the opposite of wisdom.

The second step of the eightfold path is Right Thought. Right Thought does not run towards what it likes and away from what it dislikes. It follows the Middle Way, neither liking nor disliking, free of judgment.

We left the Garden of Eden because we chose to choose, to weigh, to decide, to activate our thinking mind, thereby losing our inherent super power mindfulness. No one kicked us out of the garden. No one observes us and decides if we should be punished or rewarded.

The law of cause and effect is real. We create our own experiences. Nothing could be more obvious.

We experience our inherent Buddhahood by dint of diligent daily practice, including emptying the cup of mortal thoughts, and not engaging in philosophical or religious speculation.

This is the birthless truth, known by those who have established an authentic Buddhist practice. Only those with sharp karmic roots will understand this birthless truth and maintain their practice with diligence.

This website provides step-by-step instructions that anyone can follow, but few will. As the Bible wisely points out, broad is the path that leads to destruction (ignorance), but narrow is the path that leads to salvation (awakening).

Reaching out to grab enlightenment is a sure way to miss it. Zen teachers often tell the story of a young monk who asked a Zen master:

“How long will it take me to attain enlightenment?”

The master thought for a few moments and replied: “About ten years.”

The young monk was upset and said: “But you are assuming I am like the other monks and I am not. I will practice with great determination.”

“In that case,” replied the Master, “twenty years.”

A grasping, ambitious mind is an impediment to enlightenment.

Zen practice is not about aiming at a target and trying to hit it or setting a goal and trying to attain it.

To the contrary, Zen practice is about letting go. As the Buddha said, the twelfth step of the sixteen steps is to liberate the mind. This means to let go, to fall into the nimitta. And that leads to super power mindfulness and that enables penetration of koans and that leads to Nirvana.

In the practice of Zen, we create the conditions that allow enlightenment to happen. And then we let go and experience the Incomprehensible Unconditioned State of Ultimate Reality – and by naming it we have stumbled past it.

Remember T’zu-ming, who would stab himself in the thigh with a sharp tool when he felt himself becoming drowsy?

That’s the kind of dedication it takes to wake up.

Master Hakuin in Wild Ivy tells of a time when he and another monk vowed to sit for seven days together without eating or sleeping. They placed their mats a few inches apart and faced each other. They put a bamboo stick between the mats and agreed that if either meditator saw the other one getting sleepy, he was to pick up the stick and whack the sleepyhead between the eyes.

Master Hakuin reports that for seven days, neither monk so much as flickered an eyelash; the bamboo stick was never used.

The Buddha, having sought without success a teacher who could point the way to enlightenment, vowed that he would sit under a Bo tree until he either died or woke up.

It takes the determination of a Hakuin, a Tzu-ming, a Buddha to wake up.

Hakuin praised a book entitled “Breaking Through the Zen Barriers.” Note the plural in “Barriers.” Solving the koan “Mu!” is not the end of practice. Many koans must be passed. Many barriers must be broken through.

There is no beginning to practice, no end of enlightenment.

So for our ninth step we perform our Beginning Zen steps to put mindfulness in front of us and then we segue into Tranquil Wisdom meditation.

Bhavana Society Forest Monastery and Meditation Center

We attain super power mindfulness, or we should say that super power mindfulness appears, and we penetrate our koans, one by one, until we see It.

What happened to Moses on the top of Mount Sinai? What is the burning bush that burned but was not consumed by the flames? Why did the bush say: “I am the Great I Am”?

If we sit twice a day and master Tranquil Wisdom meditation and put super power mindfulness to work, the answer will become obvious.

Zen teachers tell us to place our attention about three finger widths below our belly button and into the center of our body (called the hara or tanden in Japanese or the dantian in Mandarin). This is the site of the third chakra in Tantric Hinduism.

Despite our best efforts, there will come a time when the pleasant burning sensation we feel in our hara rises to the top of our head. Whenever I reported that event to my teacher during a dokusan he would bristle: “That’s not Zen! Return your attention to the hara.”

The hair of our head is the burning bush that burns but is not consumed. We have left the hara and climbed to the top of the mountain, the top of our head, home of the chakra our Hindu friends call the crown chakra.

And when we feel the flame burning, we hear what Moses heard (I am the great “I am”) and we know what he experienced. It may not be Zen, as my teacher insists, but it is real.

But my teacher is right. When we feel that burning sensation on the top of the mountain, and we feel that we are the great I am, we let go of that mortal thought, that makyo, and return our attention to the hara. That’s Zen.

(1200-1253)

I once read a sign on the grounds across the moat from the Imperial Palace in Tokyo. It said, in English: “No smoking, no bonfires.” I chuckled because it was so Japanese – saying “no fires” by prohibiting fires from the smallest to the largest.

We can keep a little bonfire burning in our hara all the time. It requires mindfulness but with effort the fire never goes out.

Keeping that bonfire burning throughout the day, and not just during times of formal sitting, is a deep mindfulness practice. Whenever we discover that the fire has gone out, we return our attention to the hara and get it going again.

One way to re-start or re-fresh the fire is to recite namo amituo fo throughout the day, using it as a bellows to make the flames stronger.

Keeping the fire going is the Buddhist equivalent of the Christian injunction to pray without ceasing. If we can keep our hara or dantian glowing warmly 24/7, we are in the neighborhood of Nirvana.

When we sit for a formal zen sitting, zazen, our hara is already on fire and we can glide through present moment awareness, metta, silent present moment awareness, awareness of breaths both long and short, awareness of the whole body of the breath and awareness of the breath of the moment, the single tooth of the saw, in just a short while.

Having established mindfulness of the body, the three other mindfulnesses flow freely, without effort, and we are soon ready to solve another koan.

There are four stages of enlightenment according to the Buddha. Stream Entry (sotapanna), the Once Returner (sakadagamin), the Non-Returner (anagamin), and Buddhahood.

The Buddha taught that Stream Entry was attained when the first three of the ten fetters were overcome (the belief in an independent self -sakkaya ditthi-, doubt, and belief that chanting, rites and rituals alone could lead to Nirvana).

It is not difficult for modern people to agree that chanting, rites and rituals alone cannot lead to enlightenment, nor is it difficult to overcome doubt in the Buddhadharma; practice rather quickly removes such doubt. Sakkaya ditthi is the biggest hurdle for most of us.

A once-returner is one who has cut the first three of the ten fetters (thus attaining stream entry) and loosened the fetters of sense-desire (greed, lust, aversion), and ill will. Notice that these two powerful fetters need only be loosened to graduate from stream entry to once-returner status!

We loosen the fetter of sense desire with Present Moment Awareness and Silent Present Moment Awareness. We loosen the fetter of ill will by practicing metta.

A non-returner has cut the five fetters of belief in a self, doubt, belief that chanting, rites and rituals alone can lead to awakening, sense desire, and ill will.

Our daily practice of metta/loving kindness reduces our ill will. Our daily practice of Present Moment Awareness, and Silent Present Moment Awareness reduces our sense desire and our daily Mindfulness of the Body, the Feelings, the Mind and Mind Objects eliminates our sense desire.

The path that leads from ignorance to Stream Entry is the Eightfold Path and the path that leads from Stream Entry to the Once-Returner and to the Non-Returner is the Noble Eightfold Path according to Venerable Ajahn Brahm, because now it is a noble one who is following it.

And full enlightenment requires dropping the desire to experience the world of form, attained through the jhanas (fetter number six), and the world of formlessness, attained through the immaterial attainments (fetter number seven). And then conceit (fetter number eight), restlessness (fetter number nine), and ignorance (fetter number ten) must still be overcome.

When we drop all of the fetters, we discover that we created the fetters.

And we discover that we created the notion of a self that needed to drop fetters.

As R.E.M. says: “Oh, no, I’ve said too much. I haven’t said enough.”