I attended a meditation retreat in the late 1980s in southern Missouri with about 500 people. It was by far the largest group I had ever sat with and the effect was palpable. There were times when everyone would go into a deep meditation at the same time; it could be felt.

I recall an occasion when we are all sitting very quietly and I became aware of the clicking of a dog’s claws on the concrete floor. There were several dogs on the property, a farm not far north of the Arkansas border. They were friendly and harmless and I didn’t mind that one of them had entered the huge meditation hall through an open door. It was summer, the meditation hall was not air-conditioned, so of course the doors were open.

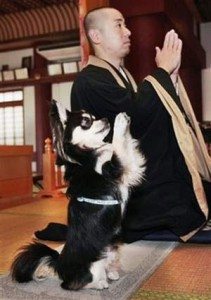

I then heard a pitiful “Yelp” and I opened my eyes. A monk had the dog by the collar and was dragging it to a door; he put the dog out and closed the door.

I approached that monk afterwards and asked him why he had removed the dog from the premises. More than twenty years have passed since I heard his answer and I have never forgotten it. I have forgotten thousands of conversations over that span of time, but this one was unforgettable.

He told me that when he was a young monk, he harbored a secret for years. He was ashamed and didn’t want to let anyone know about his problem. Paraphrasing, he said: “For reasons I didn’t understand at the time, I was killing my pets. My first puppy was so adorable it ripped my heart out when it died at about one year of age. I really grieved when I lost him. I eventually decided something must have been wrong with that puppy and I worked up the courage to accept another one as a gift. It died in less than a year. I grieved again. Another friend gave me a cat and it was so precious. It lasted six months and I realized, I thought, that something was wrong with me. I was a pet killer.”

“I went several years with no pets, certain that any pet of mine would have a short lifespan. I then noticed that a fellow monk seemed to have the same problem. He had a different pet every time I saw him so one day I told him I had noticed that he didn’t keep his pets very long. He said he was ashamed to say that he was on his fourth pet and would never own another one if it died quickly as the first three had. If this one doesn’t last, he said, I will have to admit I am an animal killer.”

“I told him that I had the same problem. We decided to contact other pet-owning monks and before long we found several more who had concluded that they were pet-killers and had stopped keeping pets.”

“Several of us decided to go to our teacher and to report to him our discovery. He dropped his head down, his jaw touching his chest, and said it was his fault and that he had to accept the responsibility for the death of each pet. He said that during our training period, he had neglected to warn us not to live in close quarters with any animals.”

“He then told us that all sentient beings have a mind-body connection and that the mind and body have to be “in parallelism” with one another. He said common pets like cats and dogs have very crude minds and very crude bodies to match. If they live with a meditator, their minds become more subtle and no longer match their bodies. With the disconnect, the body dies.”

“He told us it was OK to own pets if they were primarily outdoor pets, but even then they should not be exposed to meditation on a frequent basis.”

“The meditation in our hall today was intensely powerful. That dog would have died had I not dragged him out of there.”

I remember staring at the monk, thinking: “This guy and his teacher may both be nuts.”

Over the years, however, as my meditation practice grew, the theory began to make sense. I have often felt the crudity of my body holding back the subtlety of my mind. One day I felt that I was an overweight vegetarian, not an underweight vegan, and that my extra weight was a hindrance. So I switched to soy milk and then added almond and rice milk. I’m still not totally vegan, thanks to an occasional slice of pizza with real cheese on it, but I think the switch toward a more vegan lifestyle was beneficial to my meditation practice.

As the mind of a meat-eater becomes more subtle with sustained meditation practice, the lust for meat subsides. That’s why so many meditators are at least vegetarians if not vegans. And the most accomplished meditators I know are vegans.

So what, exactly, is the mind/body connection? Our body is a manifestation of our mind. But unlike the body, the mind is indestructible. The monk told me that his teacher had consoled him and the other monks by assuring them that their pet’s bodies had stopped working but that their respective minds survived the death of their bodies. The brain is in the mind but the mind is not in the brain.

Or, as the Heart Sutra, puts it: All are the primal void; none are born or die.

So we can take care of our bodies, and we can improve our meditation by doing so. But the body is the anchor of the mind, pulling it into the world of sense desire. So as we cultivate our minds, we must also work to make our body more subtle, lest it lose its parallelism with its mind.